Twenty, even thirty hours into Trails of Cold Steel, and you’ll still be getting to know the class of nine students that form the core cast (and that’s not saying anything of the other characters that become important later on). This is a slow burn and dense game, and, while it does require a commitment and level of patience that many would simply not have, the development team was right in their confidence to allow the exploration of characters to happen slowly, because they have a ripping yarn to tell.

Related reading: Between this and Yakuza 5 (Click here for review), the PlayStation 3 is still enjoying a hell of a twilight.

On one level, it’s the kind of coming of age story that is so popular among so many other JRPGs out there. Some, such as Final Fantasy X, explore this theme on a metaphoric level, sitting it in the background without making explicit reference to it. Others, such as Persona 4, do make the theme explicit and core to the entire experience. Trails of Cold Steel is an example of the latter, and I’m not exaggerating when I say it holds its own when compared to one of my ten favourite games of all time.

The personal journeys that these characters, pulled from every social, economic, and geographic corner of the world, is both beautiful to witness, and meaningful to muse over. At the start of the game, we witness the orientation of a new year group of students that have come to an exclusive military academy. This particular group of nine characters are told that they will form a special, experimental class, as each has potential well beyond that of their peers. Immediately they are dropped into a dangerous, live dungeon, situation, and from that point onwards they are expected to bond and work cohesively to the benefit of the group.

But that’s not easy, because there are deep cultural divides that run through the world of Erebonia, and, as I mentioned, the students have been pulled from every walk of life. Some are noble-born. Others are commoners. Still others belong to organisations and groups that distance them from the societies of nobles and commoners alike. One belongs to a Mongol-like tribe that exists outside of the empire from lands far away.

The grand “experiment” that this class is meant to symbolise is whether it is possible for individuals to break through the historical divides built into their psyche through their backgrounds and co-exist peacefully and productively with one another. For each character that involves pushing through some very stiff walls and going through a great deal of personal growth in order to become more open-minded. One boy from a common upbringing loathes nobles to such a degree that he refuses to so much as speak to his classmates that are noble-born. A girl, meanwhile, becomes hostile to another when she finds out that her classmate has a mercenary military background.

Achieving this kind of unity requires more than simply mingling the students together, and the academy that the class attends works to the theory that individuals that are forced to work together in trying circumstances can eventually overcome their differences. Part of the curriculum for this special class is to travel to various cities and points of interest in the world and help the locals deal with the issues that they’re having. Split into two groups for these missions, one might assume that the class’ teacher would separate the students that don’t get along, but what happens is quite the opposite; she deliberately groups them together.

It’s no spoiler to say that class members do overcome their differences and become allies and friends, and in each instance, the catalyst for the shift in attitude is when an event of moment of vulnerability shows that character that their classmate is indeed human beyond the socio-economic class the belong to or the background they have. It’s almost naive in how hopeful Trails of Cold Steel is in the human condition, but at the same time, that innocence is so sweet and charming, and the kind of positivity and hope I would like to see applied to the world at large. Trails of Cold Steel makes a strong argument that a great deal of the world’s racism, bigotry and hatred could simply be resolved by bringing people together so they can experience on another, and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the narrative is set at a school with students as protagonists – in the real world it is indeed ignorance born of poor education that produces so much of the prejudice out there.

Another consequence of this approach to narrative storytelling is that Trails of Cold Steel is one of the few games that has managed to turn me around on characters that I had a poor first impression of. Perhaps it’s because it takes so long to carefully develop each of the main characters, and perhaps it’s because as we watch the characters grow closer with one another the banter between them becomes quite fun, but there was not a single character in the ensemble that I wasn’t really invested in by the end. Even Persona 4 wasn’t capable of that (God I hate Yosuke). I still had my absolute favourites, of course, (Alisa is my new waifu okay… don’t tell Miku), but I found each and every one of them a worthy and interesting example of character development.

Sitting over the internal stories of the class and their tales of personal growth in Trails of Cold Steel is a sweeping epic narrative of political conflict. At first this plays out around the characters largely without their involvement, as they only have minimal understanding on what is going on, but the conflict between four great aristocrat houses and the commoners, led by a charismatic Che Guevara-like figure slowly becomes more and more their problem. Slowly they find themselves becoming more involved, slowly they start to put the picture together, and that slow development of the picture is both intriguing and consistently surprising for us as players.

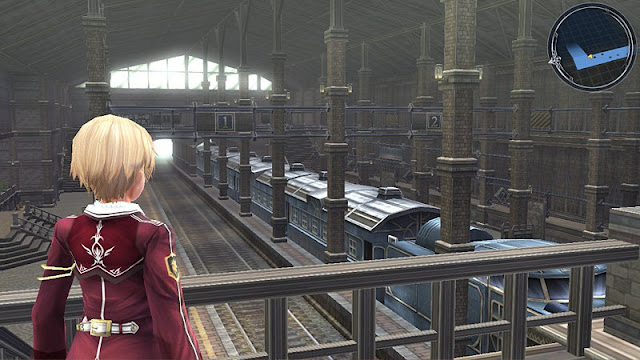

Without giving anything away (because the slowly unwinding political intrigue is really the most interesting part of Trail’s broad narrative), the Machiavellian tactics that the noble houses engage in order to keep control of society around them open up some really quite interesting political and moral philosophy debates. The world of Trails of Cold Steel is one that is enjoying an explosion of convenience courtesy of the technology and infrastructure that the ruling class has invested in and been directly responsible for. Trains allow easy transport around the nation, and people have access to foods and objects that they otherwise wouldn’t have as a result. The boarders are more secure, with armies being able to travel between points more quickly, and the cross-cultural collaborative opportunities that improved travel allows promises to lead rapid development in the arts, education, and overall culture of the nation.

Powered by “orbal technology” the people of Erebonia also see an explosion of scientific advancement, from weapons right through to more mundane things that are quickly taken for granted, such as power to the home. In other words, this is a world going through an industrial revolution, and without the stability of the nation as driven by its aristocrats, that wouldn’t happen.

But does this stability and wealth that the aristocracy is generating then justify, or even excuse, the way it wields its power, or the us-and-them social divide that they have allowed to occur? The aristocrats maintain military forces that often behave more like personal muscle squads than public servants. Corruption is rife. No one likes corruption (well, except those profiting from it, I guess). We’re certainly not meant to sympathise with what the aristocracy is doing, but if we push our emotional involvement in what is going on to a side and think about things from a more cool philosophical perspective, then there is certainly an interesting discussion around just how righteous the commoners are when they bring the country to the brink of civil war with the nobles.

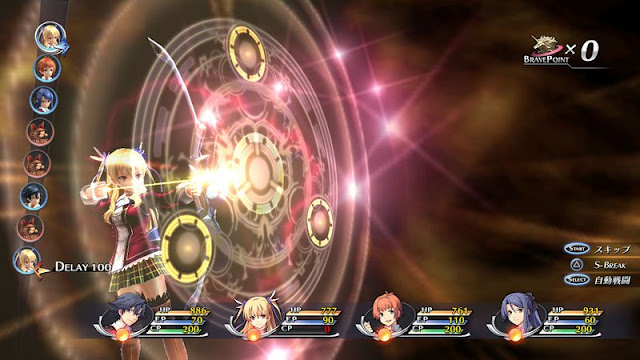

Speaking of warfare, while the combat is fairly standard turn-based JRPG fare, it does integrate its narrative themes into the mechanics nicely. Characters can “link” with one another, which produces a number of support effects that deepen the more time a character spends with the other. These support effects vary by character – one might automatically use healing magic on their ally when they get injured, while others might jump in and help out an attack. The way these links become more powerful the longer two characters are together and doing stuff with one another is a simple, but effective metaphor for the way their relationship is developing through the narrative. I do like it when a game’s combat system actually feels like a part of what the game is looking to achieve. It happens less often than it should.

With all the good work that went into creating a combat system that ticks the ludonarrative box, it’s a pity that the missions are so completely bland and arbitrary. Far, far too often they are simple fetch quests or monster hunting tasks, and for a game that already has a protracted narrative, this kind of mission grinding becomes irritating far too quickly for its own good. Trails of Cold Steel would have been far better off being as linear as a game like Final Fantasy 13; it has a story to tell, and it’s a good one, so needless side quests and menial tasks simply pull us away from the game’s real strength (and yes, if you didn’t like Final Fantasy XIII the problem lies with you. That game was brilliant).

What the game does do remarkably well, however, is in presenting players with some challenging, intense boss battles, right down to the final blow. Boss enemies tend to have a lot of health and possess special abilities that hit hard, meaning that players need to be very aware of turn order and their own resources in order to counter the worst of the boss’ power. Each character has special “super” powers that can instantly push them to the front of the attack queue, and therefore blunt or disrupt the enemy’s own attacks, but these completely deplete the character’s special energy bar, which takes a painfully long time to build up again. Because the typical boss can’t be felled by these attack in themselves (for some bosses each attack barely scratches them), players need to be very strategic about when they use them.

However, because bosses needed to be able to withstand these special attacks, they tend to have far too much health, and for quite a few of them, if you’ve been levelling right (and that’s not hard, because common enemies are pushovers), they don’t do nearly enough damage to worry your side. So victory is a little too certain, and the war of attrition as you slowly whittle the boss’ health down can be a tedious affair. In other words, when a boss is a tough, well-constructed one, Trails of Cold Steel is at its finest. At other times it’s not balanced as well as you would hope for a top-flight example of the JRPG genre.

Despite the epic narrative, the actual explorable area of Trails is quite small, with characters being automatically routed to towns that they’ve been posted at via train. These towns act as temporary hubs, and the team of heroes can then explore the immediate surroundings and delve into a dungeon or two from there. But they can never travel too far from these towns (the school puts a limit on how far they can travel from each town they’re posted in), and the dungeons tend to be small and linear affairs. This is for the best, because when the game does open up a little – such as a period where characters head into the northern plains and explore an open area on horseback – Trails really struggles to fill the environment with interesting things to do and see; Final Fantasy XIII’s Gran Pulse this is not.

And, even by the standards of PlayStation 3 games, it’s not the most technically impressive game out there. Environments are quite simple in detail, and pop-up is significant. Textures tend to be blurry and towns, villages and environments are a little too generic – we’ve seen this all before and done better. However, this is offset by some really nice character models that, while also simple, do a really good job of capturing and enhancing the personality of each of them. Especially Alisa. Yum.

While simple in presentation, the grand scope of Trails of Cold Steel’s narrative is really what drives this game, and it does so with remarkable intelligence and confidence. You’ll need a good block of time to actually play through this one, but for people that do make the commitment to it, the rewards are more than enough.

Note: It’s worth noting that this is effectively half a game, with the final scene ending on such a cliffhanger that it couldn’t possibly be considered satisfying self-contained conclusion. Luckily the sequel is confirmed for a localisation, so while you’ll need to be willing to drown hundreds of hours of your life to work through them both, you need not fear being left in the dark in picking this one up now.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief