When I was a child, I remember watching a film about the apocalypse. Not in the sense of literature like The Road, or games like The Last Of Us, though. This apocalypse had simply emptied the world of people, so that all that was left was one family, journeying through the end of times.

I literally remember nothing more of that film. I don’t remember its name. I don’t remember the rest of the narrative, the characters, or anything else. I was very young and it was a daytime TV film that I had happened to sit down as it started for some reason. For all I know it was an absolutely terrible film that would be lucky to have an IMDB listing. But I remember that film for a very simple reason. The atmosphere of complete loneliness, of the absence of life, and most particularly, the utter stillness when there is nothing moving, all impacted on my young psyche quite significantly.

I mention this film now because Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture is very much a game that plays on that fear of a nihilistic nothingness. It’s a horror game without jump scares – a game to shock and shake the intellect rather than jump the physical body. It’s a work of poetry with few words, but deep emotional weight. It’s a treatise of existentialist theory while also being the prettiest game, bar none, that has ever existed. It is nothing short of breathtaking.

You play as an nameless, formless observer that has come to a quaint little English countryside hamlet in the wake of some massive-scale disaster that has destroyed all life around it. Birds don’t chirp in the trees, and bunnies don’t bound across the road as you might expect in this kind of setting. What is eerie is that none of the environment has been damaged. It’s a ghost town that looks like it was lived in as early as yesterday. What will immediately put you on edge is the occasional sign that something bad happened in this little village – you’ll find bloody tissues on the ground, or doors that have quarantine signs plastered all over them. In a simpler, less intelligent game, you would immediately expect the zombies to come leaping out at you from around the corners.

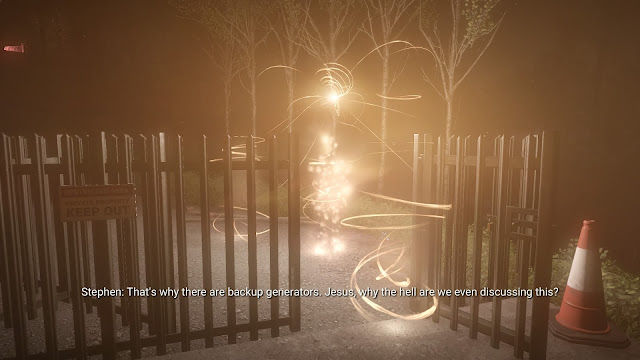

But there are no zombies. The closest that you’ll encounter to an enemy is a mysterious glowing ball of pure light and energy that will zip around haphazardly, angrily, and if you get too close to it you will hear crackling, angry voices and pulsating static. But you’ll eventually follow the path that this glowing ball takes, and you’ll come to realise that it is, in fact, your guide through one of the beautifully melancholic stories we’ve seen told through the games medium to date.

As you follow this glowing ball, you’ll periodically run into barely human-shaped ghostly apparitions, also built of a glowing orange light. These encounters will be a little confusing at first, as the game doesn’t have a tutorial to explain how it plays or how the narrative is told, but then you’ll figure out that these ghosts are re-enacting the last days before the disaster that removed life from the area (and, it is strongly implied, the planet). Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture then settles down into a rhythm where the narrative is broken up into “chapters” in which you’ll follow the story of one of a handful of major characters and their last moments on the earth.

Despite the impending disaster, most of these characters have no real idea what is going on, and go about their lives largely unworried about the world, other than the rumours of disappearing people and a flu epidemic. Instead, they are worried about the love lives of their children, the presence of a “foreigner” in their nice, traditional village. Their beloved birds dying. Their struggles with religion. These could be stories of anyone reading this review right now, blissfully certain that a tomorrow will come and life will go on. I won’t spoil specifics about these stories, because if you’re anything like me, the emotional weight of how it will all play out will make you appreciate your own family, loved ones and friends that little bit more, but I will say that these stories had a profound, meaningful impact on me.

It was unfortunate that in its last act Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture struggled with bringing things to a memorable conclusion, but it is a difficult, complex kind of story to draw to a close, and there’s a palpable sense of unresolved inner conflict in the writing of it itself. On the one hand there’s a near spiritual reverence for the lives of the deceased, with the transitions between chapters being marked by a short journey across a path of lights in the dark. It is strongly symbolic of the concept of a person’s transition from life to the afterlife, and journeying across these paths is almost like following the spirits of those that have passed, before a new chapter starts and your observer body is wrested back to the “real world,” to follow another life.

At the same time Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture carries with it the existentialist weight in questioning God and the meaning to life. Individual characters are repeatedly critical of religion, and then the narrative itself is built around making us wonder what the purpose of it all is when, at some stage, we’ll simply disappear, along with all those around is. The creatives at The Chinese Room aren’t able to answer any of the questions that they posit through the narrative to any meaningful level, and in turn that means the conclusion is relatively unsatisfying, but the way that it asks these questions and develops its characters are truly evocative and heartfelt.

Most fascinating of all, however, is how indeterminate your own character is. Nameless, voiceless, and unable to interact with the world (other than by opening unlocked doors and pressing the occasional button to hear a radio broadcast or phone message), one of the biggest existentialist questions posted by The Chinese Room is the role of the player’s character in this all, and indeed what purpose that player has for existing. There’s no way to affect how the story plays out, and indeed what will happen in it has already happened. And yet everything happens only when you activate it (by approaching the spot where a scene plays out). So are you, in effect, God, playing witness to the lives of humanity but unable to (or unwilling to) participate? Or is The Chinese Room simply making a comment on interactive games of all persuasions and the illusionary sense of freedom that they enable? It’s a question to ponder over, for sure.

Supporting the narrative is, as I mentioned previously, the most beautiful art direction we have ever seen in a game. Every building, every step, and every rock, river, tree, and corn field is meticulously designed to inspire awe and wonder in the player. From the township, to the farm fields and sports fields, I found myself marvelling as much in the details of how The Chinese Room has been able to recreate the life and environment of a small town, as the wow moments where I would get a view of it all from on high. As someone who grew up in a small town (in Australia, but Australian small towns are strongly influenced by English culture), I was hit by more than a few waves of nostalgia, from the way the town hall and church were designed, right through to the developers understanding what roads would be concrete “main” roads in a small village, and what would be left as a dirt track. And to give you an example of just how deeply this attention to detail goes – at one stage I laughed out loud because I saw a blackboard in the town hall that had “orders of business” written up on them that only a local rural community could possibly concern themselves with.

What disappoints me most about Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture is that The Chinese Room had to come out and explain to everyone that there was a “run” button, because people were complaining about the movement speed of the character. It’s not so much that this disappoints me because I thought the player character did move at an adequate pace (which I do believe, given that the game is quite upfront about what it is, as a slow-paced narrative experience). No. What disappoints me is that in this game there are so many conversations we can have about it – about some of the themes I have outlined above, and then plenty of others because this is one of those examples of art where meaning is open enough that different people will draw their own conclusions from it. And instead so much conversation was dominated about how fast players can run through the world.

I can appreciate that some might find the movement too slow, especially on a second play through, and especially to trophy hunt, because the game all-but demands that you travel to all corners of its fairly large open world in order to unlock everything. Without the narrative keeping the player moving in a steady direction forwards and encountering new story elements regularly, I can imagine that Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture is too slow. But that’s fixating on the most tiny and irrelevant failing. Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture is a narrative game and that’s the bit that should be discussed.

The Chinese Room has managed to create one of the most insightful, meaningful, and emotional games that we’ve seen in some time, perhaps forever, and bravo to Sony for taking a real punt with something so completely arthouse. This game is a major win of exclusivity for the PlayStation 4, and frankly, if there were more games like it being published and pushed into the public eye by the major publishers, than more people from outside of the games industry might be inclined to take games seriously as works of art.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld