I wasn’t sold on Splatoon at first. I had no love of the modern children’s cartoon aesthetic that I saw in trailers and video, and while I did appreciate that Nintendo was looking to get involved in the shooter genre in a more family friendly, bloodless, and original way, I wasn’t sure that a “capture the territory” type game would get people on board. Especially when the entirety of what Splatoon was offering would be one of a half dozen (or more) gameplay modes in a Battlefield or Call of Duty game.

But then I started playing, and everything Nintendo was looking to achieve in Splatoon made sense. Nintendo has crafted a meticulous and focused little game here, and it drips in raw quality from start to finish. For a genre that has traditionally focused on intensity, speed, and raw, unabated violence, Nintendo has managed to create a shooter that is as similar to the Battlefields of the world as Smash Bros. is to Mortal Kombat. Splatoon is innocent fun. It’s nostalgia from the time as kids where we’d have water pistol fights and allow something as simple as that occupy us for hours. It’s a game that both children and adults can enjoy, and it achieves all of that while also being a highly refined, balanced, and competitive game.

In short, Splatoon might finally be the shooter that I keep coming back to after I’ve finished writing my review. It might finally be the first example of its genre that isn’t immediately relegated to the bin of discarded game discs once I sign this article off. Nintendo may just have achieved the impossible and actually got me to enjoy a shooter. That’s huge.

Even more impressively is the game has no single player mode worth bothering with, and yet I’m a guy who would usually rather play a visual novel than other multiplayer-only games like League of Legends. Narrative is generally deal breaker for me, but Splatoon gets away with almost offering nothing there. Sure, there’s stuff you can do as a single player experience, and I nuttered about completing the various objectives in that mode for a little while, but it really was nothing more than training for the main event, the multiplayer, and once I got stuck into that, I didn’t go back.

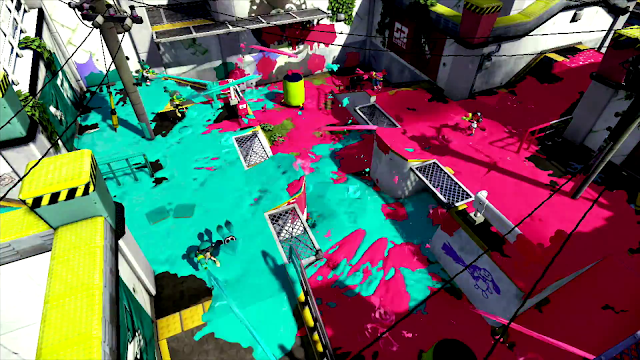

Splatoon is in many ways an indirectly competitive multiplayer shooter, in which players will be more focused on using their guns – which squirt ink – to “paint” the floors and walls of the level, rather than firing at one another. The goal of each match is to paint more of the space than the opponent, and while some direct competition is necessary and levels are small enough so that opponents will bump into one another as a matter of course (and they will shoot at one another when this happens), this structure means that even when there isn’t an enemy to fight, you’re still actively doing something more interesting than running around and looking for someone else.

Player-vs-player combat, when it happens, is over quickly so the intensity doesn’t build up too much to start to feel stressful, and is, of course, completely bloodless. Lose a “gun”fight, and you’ll simply disappear off the screen and be returned to your team’s starting position. Splatoon matches are short, but active affairs, and again, the intensity never quite builds to boiling point. Nintendo would never risk allowing voice chat to allow people to hurl abuse at one another, but even if they had I suspect this online community would be better behaved since the stakes never seem quite as dramatic as they do in a Call of Duty game; Splatoon is here so people can kick back and have fun, not engage in a life-and-death match to improve the kill/death ratio.

This also seperates the game from other brightly coloured and child-friendly shooters, like Plants Vs. Zombies: Garden Warfare. In that game characters and weapons still behaved like their counterparts in Battlefield, they just had a cute PvZ-coloured coat of paint over them. In Splatoon, Nintendo did much more; its focus on painting the landscape also forced its developer team to re-think how weapons would work in order to keep them relevant as objects of mass painting. The sniper rifle is still slow to fire, but now it creates a great long line of paint across a fast distance. The melee weapon has been re-invisioned as a roller, which paints quickly and does a lot of damage to an opponent who happens to be caught up in it, but has trouble splattering ink at a distance, and that’s becomes an issue when the player wants to use his/ her squid form to travel quickly through the ink. In squid form a character literally turns into a squid and dives into the ink that his or her team has dumped on the space, and by doing so they’ll recharge the inky ammuniition for their weapons, and move faster across the map. One of the most effective ways to move quickly is to shoot ahead, turning the space in front of the character into ink, and then diving into it to move forward quickly. That option (and thus some mobility) is lost to a player with the melee-focused roller.

The ink system adds so much to the game’s strategic depth. Suddenly, and in a very abstract manner, Nintendo has actually implemented supply lines into its shooter. Such a core (and important) military strategy has been largely absent from military shooter games, and of all games it’s Nintendo’s bright and colourful watergun game that finds a way to bring it into the genre. If you’re stuck behind enemy lines, you’re going to be slower and struggle to keep your weapons fully supplied. You can create small pockets of ink for yourself, of course, but you’re still restricted and likely stuck in a sea of the opposition’s ink. You’re not going to be of much help to your allies, and you’ll also be knocked out soon enough, as you’re basically helpless. The only real chance you’ve got of surviving is to somehow break back through and rejoin your own side’s line. There, in the company of your own teammates and with an ocean of your own ink to swim through, you’re be effective again.

With only four team mates per side, effective teamwork is necessary to be really successful in Splatoon, but with communication being so limited, the game never quite delivers on its promise for highly strategic play. I totally appreciate Nintendo’s decision not to allow voice communication in order to keep Splatoon a positive, friendly experience for players of all ages, and I do like being able to log in knowing that I’m not going to be exposed to some idiot child hurling homophobic abuse at me while playing bad rap music in the background (as happens inevitably with every other shooter I bother going online to play), but on the other hand, the number of stock communication phrases you can use in the heat of battle are limited, and people generally ignore them, even when you spam the “come help me” command. There is potential for Splatoon to become a highly strategic team-based game, and perhaps the community over the longer term will become a more strategic one as it settles down and the veterans are left behind. For now, however, the typical match is a free-for-all, and not quite living up to the potential of how Nintendo clearly designed it.

And as much as I have grown to love this game for its sheer, unbridled sense of fun, I’m still not sold on the aesthetic direction. In fact, it reminds me of Disney’s fall from grace as far as its children’s material is concerned; when it went from the beautiful, evocative hand-drawn art of the likes of Winnie the Pooh to the modern, generic and emotionally plastic 3D models of today. For Nintendo to go from the distinctive and classic Mario and Zelda franchises to this try-hard take on American “punk kid” culture leaves Splatoon as anything but pleasant on my old-man eyes. I’m sure others will appreciate the vibrancy and energy of it all, though. And hey, I’m still playing, so I’m obviously not that offended by it, even if I’m not enjoying the art.

For a new IP, Nintendo has done everything right in Splatoon. It has forged a game that has an identity that is uniquely its own in a market and genre that is absolutely saturated in me-too nonsense, and has shown us all that there’s no reason that a shooter should stick to template: it’s okay to be different. Take note, EA and Activision, it’s okay to be different. Splatoon is almost endlessly replayable, and it effortlessly my favourite Nintendo game so far this year.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld