As I suspect most readers of Digitally Downloaded are aware, for the past year-and-a-bit I have been working on a book about games. Called Game Art, it’s a book of interviews with various game directors, producers and artists, presented as essay-style discussion pieces, and accompanied by visual art works from the various games that each of the directors have worked on.

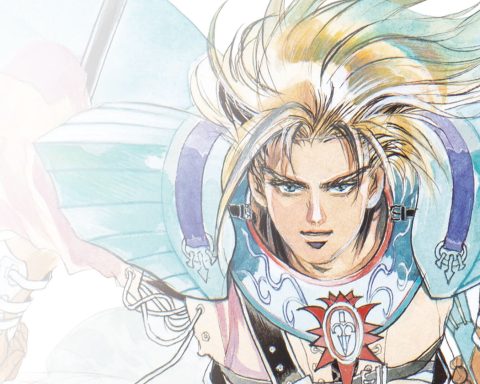

The book’s about to go into the printing stages ahead of its release in a couple of months, and I wanted to use the opportunity firstly to share with you what will be the final cover (exciting stuff! I hope you like it), and start opening up a dialogue about the book up with readers. In the coming weeks and months up until the release I’ll be writing more articles related to the various games under discussion in the book, and I wanted to encourage everyone to ask me follow-up questions or any other queries they might have about it.

But first I thought I’d share the reasons that I decided to write this precise book, and what I hoped to achieve from it. It has been something I’ve wanted to do for quite some time, so obviously I hope it resonates with people, and after reading through, if you do have any other questions, please don’t hesitate to ask me!

And so, without further ado:

Games Are Art

This is a book that I have wanted to write for many years now, because I have felt for some time that if there is one area of discourse that is really lacking in depth in the games industry is that it’s the ability for game artists to talk about what is important to them as artists. In a typical media interview with a game designer he or she is inevitably asked to talk about whatever game they are working on, or possibly the business behind the game. Very rarely does a game artist get to talk about themselves, what drives their work, and the themes that are important to them.

For many and varied reasons video games still face a legitimacy issue when it comes to academic debate. But these debates are held away from those who are making games. In reality games are a creative outlet, and increasingly game designers are using their work to make a statement, or express something of personal importance. This book will not argue that games are art; it simply accepts that to be the case.

Art is a work that has cultural or personal importance. As an emergent media, games are occupying an increasing part of many people’s lives across the world, whether that is as a five minute time filler on the phone during the morning commute, or the most complex of RPGs and strategy games that require hundreds of hours to master. As such a permanent, everyday part of peoples’ lives, what better way for a creative person to get his or her message out than through a game? Paintings are housed within galleries, films are expensive to produce, and literature lacks a visual component that is key for many stories that many people want to tell. Games are relatively cheap to produce and can sit in a person’s pocket.

Games are visually beautiful. Games are a dance, where the player navigates a space to a carefully orchestrated soundtrack. Games have meaning. They have been used for activism and to express philosophical viewpoints. Games are, ultimately, nothing more than a tool, and while the body of criticism out there on games focuses on how entertaining they are, the reality is that, just as with literature, film, theatre and music, we can read much more into games than how much fun we had playing them.

The Eureaka Moment

The first time that I came to the realization that games had some kind of academic merit was when I came across Atlus’ Persona 4 on the PlayStation 2, just after I had finished studying new media as part of an undergraduate degree. Being a poor (and time poor) university student I only had so much money to buy so many games, so I would generally pick up one or two RPGs over the course of the year, as they were usually quite long and I would get my money’s worth.

So I started playing Persona 4 and immediately I found it to be a thoroughly entertaining, albeit somewhat standard Japanese RPG. But something stuck with me for weeks and months after completing the game; I kept coming back to its narrative, and decided I would play the game again to see if I could pin down precisely what it was that I found to be so special about the game. As I worked through that second play through, I noticed that a lot of the themes that I had studied during film, theatre and literature units were featured in parallel in this game, and in similarly complex ways.

Persona 4 is a game of nostalgia; a title that speaks to the desires of many Japanese people to return to the nation’s previous culture where there was less of an extreme emphasis on mass consumerism. It’s a social criticism of the impact that technology has on our lives; in the game characters “enter” a TV and when they do so they’re able to manifest their personal fears and shames as, literally, weapons. They do this in the pursuit of solving a series of crimes; a literal attempt to understand events in the world around them.

But it’s also Nietzschean philosophy in application, and it was only after I’d done some study on the great German philosopher that I truly understood what Persona 4 was really on about. Nietzsche’s concept of the fog of pride is represented in Persona 4 as an actual fog, and when in the TV world, the characters are in possession of glasses that allow them to cut through the fog and see reality for what it is. It is only by doing that that these characters are able to come to the truth and realise the truth about themselves and the world around them. As the fog turns deadly and starts to threaten the real world players are confronted by single, serious moral question, and it’s then that everything that the game had just spending the last 80 hours or so building up to begins to make sense. The Nietzschean sense of morality comes to the fore, and players are challenged on both an intellectual and personal level.

It was that final act in Persona 4 that made me realise that video games are in a unique position to deliver the same wide range of quite mind-bending themes that film, paintings and literature, in a manner so deeply personal to the player that the other media couldn’t hope to emulate it. Persona 4 has three possible endings. The first ending is based on making an answer to the Big Moral Question, and that result, while unpleasant, provides closure. The second ending yields an epic final fight, and then the game experiences a conventional ending where everything in the world seems to be set right.

And yet there remain questions. Questions that can only be answered by going out of your way to track down a hidden third ending, which will tie up all the loose ends. This ending doesn’t happen by accident, and many players of Persona 4 will never know of its existence. Many won’t even necessarily care that this ending exists; the fact that the big bad monster has been dealt with in the second ending will be enough for them. But this is the precise point that Nietzsche was making in his commentary about the fog of pride (or complacency), and the dangers of thinking you know something; we don’t fully know anything so long as we have the arrogance to assume we understand the world around us. As long as we, as players, accept that we “know” a game finishes when we complete the set of criteria that the game lays out for us, we can’t properly understand Persona 4.

That revelation made me realise that games have real merit; as works of philosophy, as expressions of creative ideas, and yes, as a wildly entertaining way to access these ideas. From that point on I have wanted to start writing about games as something more than pieces of entertainment; to show that there are ways of thinking about games that go beyond how entertaining the game is, and moreover, to show some of the thinking that goes into games from their creators.

Game Developers As Artists

One of the common arguments that I’ve heard against game developers as artists is the fact that in game development, no single person acts as an individual (unless they’re a one-person independent developer, of course). The nature of this media is that game development is a collaborative environment, and with no single cohesive vision, the end product is one that lacks in the kind of vision that produced the Mona Lisa, Shakespeare’s Plays or Orson Wells’ Citizen Kane.

But if that’s the case how can such groups explain some of the people who are interviewed in this book? Goichi Suda’s games, for instance, are instantly recognisable as a Goichi Suda game. Square Enix, with hundreds of programmers and artists, managed to create two entirely different games in Final Fantasy XIV, and then the rebuilt Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn under Naoki Yoshida. The original was by all accounts a bomb. The remade game is a darling of the MMO genre.

And then, of course, there’s American McGee, who has developed a reputation for creating games based on fairy tales that is so ingrained within his persona that fans are disappointed when his name is attached to a project that isn’t some dark reworking of a fairy tale. There are interviews with all three developers in this book, and I would challenge anyone who believes that their unique vision and sense of creativity hasn’t been the predominant factor in their games turning out the way they have.

So I would argue that the great game developers working in the industry might well work in a similar organisational structure that the great filmmakers such as Stanley Kubrick, Orson Wells or Tim Burton operate or operated within. These filmmakers are undeniably artists with unique styles… and they also headed up teams of dozens of people. Certainly there are manufactured games, just as there are manufactured films and music at the top of their respective charts. Games are also a commercial business and in many instances people are happy to simply consume “snack value” games. But the point here is that those games don’t represent the entirety of the industry, and each and every artist interviewed in the book has a unique vision that is reflected in their games.

It is often said that the games industry reflects the film industry of the 40s and 50s, where the industry is moving beyond being a simple entertainment gimmick, and emerging as a major popular art form. Just as film pioneers understood how to work with colour and established rules for the framing of scenes and the right camera angles to work with to ensure a successful film, so too are now are those in the games industry coming to an understanding of what works, what does not, and how to best express ideas through the experience.

Furthermore, just as the film industry in the 60s through to now has increasingly opened up to independent artists with smaller budgets thanks to the cheaper costs of equipment and production, so too is game development opening up to people with small, or even non-existent, budgets. Digital distribution has meant that games such as Contrast, Tengami and Luxuria Superbia are all possible that wouldn’t have been possible a decade ago when the only distribution channel was to sell the game at retail.

It is these independent game developers that really push the creativity of games forwards. Just as it is the independent and foreign film industries that often inform Hollywood, so too will we see the independent game developers, and the innovations that they come up with, will inform the development of the blockbuster games into the future, as the big studios find ideas that they like in popular independent games, and these ideas become canon. The games industry can only become healthier, both in terms of artistry and commercial viability, as it continues to mature into the future.

So, as I said at the start. This book doesn’t make an argument that games are art. It demonstrates it by going straight to the source, the artists, and allows them to talk. This book is not about games being attractive (though certainly beautiful games are artful), but more it’s about ideas, and how game directors, artists, and musicians express these ideas in their own way.

Game Art itself is not hard-and-heavy academic writing. It has been designed to be an enjoyable read that showcases creativity across a wide range of games, and has plenty of beautiful art to show some of the great work that’s being done in the industry. But more than anything else I hope that after reading this book, people are inspired to think about games as something more meaningful than a way to pass a couple of hours – that the people who work in the games industry have stories to tell that are every big as meaningful and worthwhile as the greats of literature, film, music, theatre, and the visual arts themselves.

If this book sounds interesting to you, please do pre-order it! It’s available on:

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld