It’s becoming increasingly rare to see a game that fully innovates within its genre, instead of merely borrowing and adapting what has worked before. The Evil Within comes at a time of resurgence in the survival horror category. Several recent releases, whilst attempting to capture the essence of the survivalist experience, have simply become a pastiche of zestless, horror cliches. Meanwhile, sirector Shinji Mikami, the creator of the Resident Evil series, has clearly intended to bring survival horror back to its roots by making The Evil Within.

That these roots have become so entangled around a history of staid, reused ideas make it no small wonder that his game flourishes as a unique experience. Despite its refusal to wholly abandon the lazy rubber stamping of modern horror stereotypes, Tango Gameworks has revitalised the genre with the survivalist mechanics of The Evil Within.

The story is ubiquitous enough in horror gaming. A detective arrives at scene of mass slaughter in mental asylum, whereupon he and his team are ambushed by a malignant spirit. That detective then awakes in temporally shifting ‘anti-world’ where creatures called ‘The Haunted’ are enslaved in murderous pursuit by an omnipotent demonic force. You play as said detective, one Sebastian Castellanos, and traverse through horror filled locales that act as allegory to your enslaved and tormented mind.

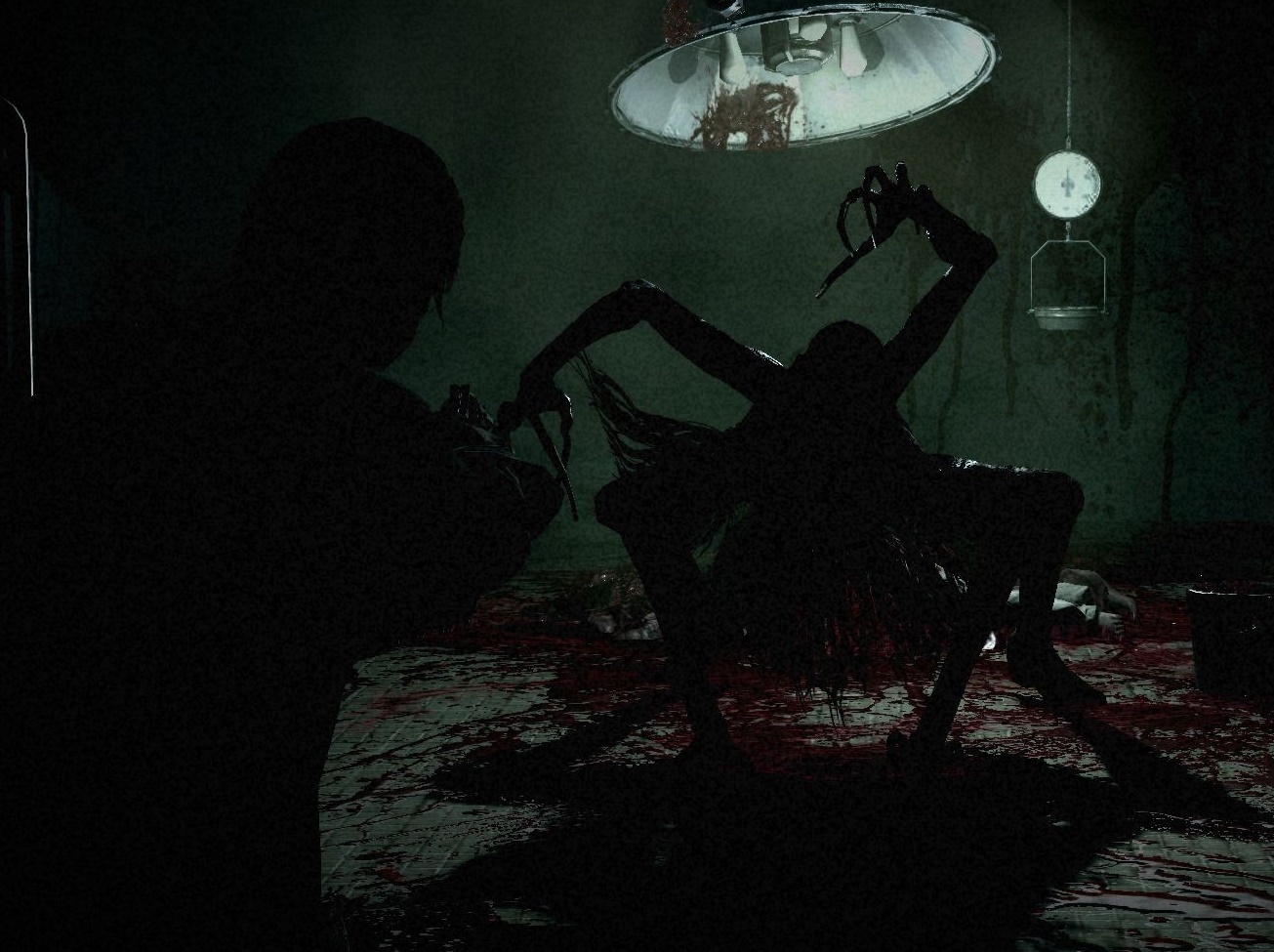

All the regular stylistic horror stereotypes are articulated competently enough; the tortured origin story, the haunted mansion, the dark foreboding family portraits, the grunting heavyset chainsaw wielding pyscho, the abandoned barn, the bloodied pitchforks etc. We are inundated with the irreconcilable pairing of metal and flesh (Hellraiser), the faceless horror of deadly machines (Saw), and the freakish corruption of childhood (Japanese horror). The game’s influences are clear from the start. The art direction is a subtle application of grainy film stock, high contrast lighting, and diverse camera angles that incorporate tilts and zooms reminiscent of noir films, early Twilight Zone episodes and British Hammer Horror.

The artistic elegance sits alongside the game’s oppressive themes and claustrophobic level design to culminate in a game that looks as beautiful as only horror can become: that point of impression before decay, where death becomes art, before awe gives way to repulsion. It feels like you’re moving through the game by way of turning the pages of an illustrated book, so detailed is the artistic style, and so slowly and precariously do you make progress.

Occasionally the game borrows too heavily from existing horror franchises, relying on the lazy overegging of torture porn, or the off-key carnival music that plays as a theme to innocence lost. These are old ideas and we have become inured against their terror. The rusted blood soaked meat hooks, the swarms of cockroaches, and the exposure of viscera, blood, brain and bone. The freakish now becomes familiar as we become desensitised to the way games handle gore. When giving lobotomies to seemingly conscious decapitated heads in Chapter 9, I was more fascinated by the intricate design of the level and its experiment than I was appalled or nauseated by the spectacle. Maybe that’s just me, but oftentimes, at least aesthetically, The Evil Within can suffer from this fatigue of fright.

The lens through which we approach The Evil Within is already too diffuse with the unrealistic expectation of terror, to enable the game to succeed on its thematic horror alone. At first it does feel problematic that Sebastian is never fully scared, never faltering in his running or walking animation. He moves with a quick stepping skip that seems at odd for a man so frequently mauled, and so often stalked. “I sure as hell don’t want to go back in that water anytime soon”, he quips after escaping some underwater monstrosity, never fully affected by the horror he witnesses. He normalises his surroundings with Americanised slang, his everyman reaction cheapening the experience for him and for us. Fear should never induce sarcasm in a horror, only panic.

Sebastian’s dialogue sanitises the game a little, and sometimes strips frightening encounters of their potential. In this way, the inglorious task of fully walking in his terrorised shoes is denied to us as players. But the game doesn’t need the first-person heavy breathing of Outlast to be involving. We don’t have to empathise with Sebastian to be engaged with the mechanics of his travels. The Evil Within’s ultimate resonance is that terror comes not from what we are forced to see, but in how we are forced to play. This, it seems, is where survival horror finds its form.

The Evil Within excels in the objective of survival by forcing you to streamline your play, through risk reward. This will appeal to those who enjoy honing their mastery over the game, like the incremental whittling of stick into spear. The game’s precision focus on intense resource management forces a planned approach to edgy combat. There are always uncomfortable choices to be made in the game. Explosive weapons such as shotguns require cunning to use their limited ammo effectively. At what point do you sacrifice your three slugs for maximum gain? Do you salvage essential ammo-making equipment by disarming traps that could kill you, or do you use the traps themselves against the enemy and lose the salvage?

A genuine fear of failure leaks out of almost every deadly choice. Played on Survivor mode (the recommended setting) enemies are utterly resilient and ammo drops are meagre. There are ample opportunities to fail. One bullet misfired at the start of a section can mean an empty barrel when you most need it twenty minutes later. There are plenty of games in which love is born out of loot, but this is the game that makes finding a bullet more pleasurable than spending one. It has more in common this way with The Last of Us. It also forces on the player a greater tactical consideration of level design than similar survival horrors with more available ammo like Dead Space.

Sebastian suffers physically; he will go down in two or three hits and with a wide variety of deaths. His hand wobbles as he aims the gun. He can’t sprint very far without pausing to catch his breath. In these moments (the breath catching animation, the shifting reticule, the small sprint distance) do we so keenly see the man against the monsters and their threat is made more real. It’s here where you stand on a knife edge, almost always about to die. Although they sometimes feel overwhelming, multiple deaths in the game do mean something. Failure. Repetition. Improvement. Enlightenment. Progression. Blood is never spilled without a purpose, as you perfect your gameplay with each new attempt. Its steep levels of difficulty and relentless inundating of powerful bosses create a sometimes irascible experience in the last third of the game, but it never diminishes from the moments of pure immersive abandon that the game as a whole delivers. The meat of the game tastes so good that any ‘off’ parts never linger.

The arsenal available is a standard affair of handgun, shotgun, sniper rifle, and grenade. An Agony Crossbow received early in the game provides an array of craftable bolts which add environmental damage to the projectiles such as freezing ice, electricity and blinding light. Headshots and aiming are crucial to conserve ammo and prevent otherwise downed enemies from reviving. You can also burn corpses with rarely found matches to ensure the dead stay down. Lighting a match in this way makes for a melee execution twice as satisfying as the Dead Space stomp (which is also copied less effectively here). If you time it right you can set alight enemies who walk into burning corpses. When limited offensive capabilities like a match can be used so effectively, the game shines. When The Evil Within is played effectively, the game makes you feel like a skilled survivor, ingenious and tough, forever thankful but never off-guard.

Each level, Sebastian can return to a hospital waiting room area through eerily cracking mirrors, where he can upgrade his abilities and weapons using green gel found on the way. He also has the opportunity to open highly valuable loot lockers with keys that are hidden deceptively throughout the game. This makes this ‘hub’ area feel necessary and enjoyable to return to. You never know what loot the lockers will contain. Opening one always feels like the final present at Christmas, weighted with both expectation and false promise. Collectibles, conversations, and a slowly unveiling world lore provide more reasons to revisit the area alongside the gift of being able to save your game.

The Evil Within provides us with highly tense and captivating horror encounters through a graphically rich world. As such, the game invokes an uncomfortably exhilarating gameplay space that edges you toward dramatic creature encounters. Stand out chapters, stripped of their troubling end bosses, can be so relentless in their pace, so brutal in their level design, and so exquisite in their dark creative tone, that it’s hard to imagine a finer video gaming experience. This is not a game for those who like to run and gun, or who are disheartened by a threadbare checkpoint system. Those looking for the jump out scares of Outlast’s first few hours are also going to be disappointed. The true evil within this game is its clever ability to taunt the player rather than scare the viewer. Be prepared for it to look in the deepest darkest recesses of your ego, the voice inside your head that motivates you for a more perfect run, a chance to do better than you did before. It provokes the nagging monkey that says you’re a failure, and always will be. It asks you to better yourself in pursuit of perfection.

For all the games’ narrative themes of consciousness-probing, identity-subsuming science, the reordering of the psychic self for a greater application of the flesh, I needed to look no further than my own pathological gameplay in its honour. The rage quits, the restarts, the late nights, the infinitesimal adjustments to my thirteenth, fourteenth, fifteenth attempts, all part of my drive to survive to the end, no matter how many hours of hell it took. That is the essence of survival horror. Those are the roots around which The Evil Within is so expertly entwined.

– David W.

Contributor