Review by Matt S.

Review by Matt S.

I cannot believe that anyone would take a look at the Persona series, which has surely been one of the most difficult set of JRPGs to create, and think that it was a good idea to copy the theme of those games wholesale.

When I say “difficult,” I do mean that the Persona games are philosophically dense, and require narrative storytelling skills well beyond what the typical game development studio is capable of. Nihilism to Nietzsche, consumerism to nostalgia, romance to religion, the Persona games are so loaded with meaning that I am certain that in the future postgraduate students will be using them as the subject of their PhD thesis’ (if they haven’t already). It cannot be easy to take the ideas the drive the Persona games, and replicate them in a new IP.

That’s exactly what Aquire has tried to do with Mind Zero. The studio is not a stranger to intelligent game design; it worked with Sony on Rain, which was in its own right an incredibly deep game. But I do think Persona was a tough ask, and Mind Zero comes off as second best.

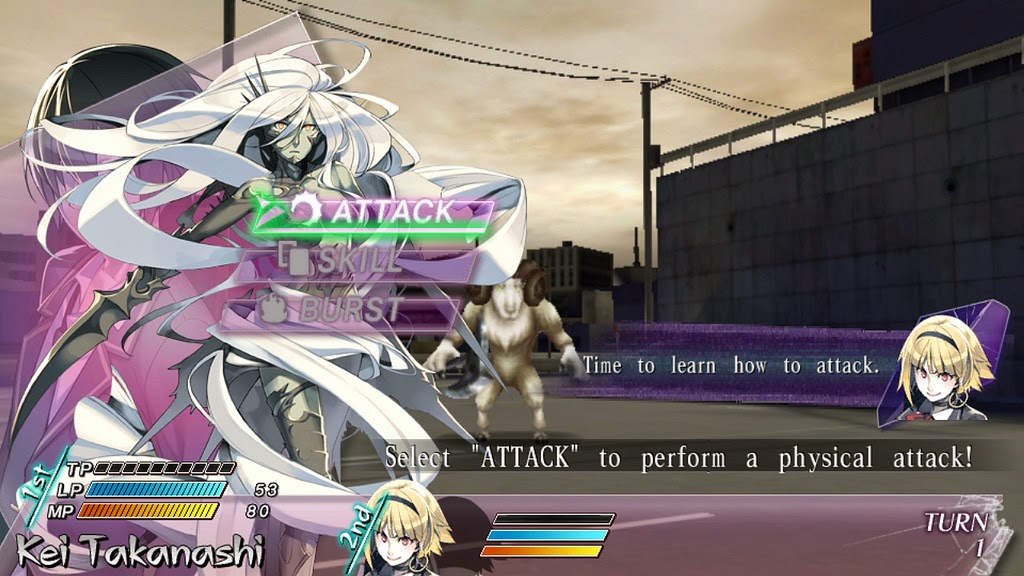

The concept of the game is that players are in control of a group of minders; special humans with the ability to summon a MIND; a manifestation of their mental strength, and then use these MINDs to battle other, wild MINDs. Thematically it all works a little like the personas of Persona; these creatures that do the battling are manifestations of the character’s will and personality, and so they each adopt visual traits representative of the character’s personality. Regular humans can’t see these creatures; the war takes place in the shadows in a spirit world that looks eerily exactly like a chain of explorable dungeons.

There are some great ideas at work in Mind Zero. As with the Persona series it wants to keep us thinking about a wide range of themes as we grind through swarms of enemies in a standard turn-based combat system. The idea behind the MINDs, which are a nice way to literally represent the capabilities of the human mind, has a nice impact on the game’s mechanics, too. Characters can summon their MIND to fight for them. When they do this the MIND takes damage, not the character him or herself. If the MIND’s health runs out, then the character is exposed to damage. Because the humans themselves are quite fragile, this combat system quickly develops into a fascinating tale of resource management, as players try and work out how to best preserve their MINDs for long-term use.

As characters level up they can equip an increasing number of “skills,” which are earned in battle or found in chests. Players have complete control over which characters wield each set of skills, so the customisation options in Mind Zero end up being quite impressive. By around level 20 there are so many different ways to customise a character that people that like to play with statistics to form a ‘perfect’ party will be in seventh heaven.

The enemies are a little repetitive with multiple dungeon levels holding the same kinds of enemies, and those enemies are palette swaps all too often. Coupled with an encounter rate that is positively primitive makes Mind Zero a frustrating grind at times, but the game is certainly challenging and has the odd environmental puzzle to break things up, and so as a dungeon crawler it joins Demon Gaze as a mechanically sound example of the genre on the Vita. It lacks the beauty of Demon Gaze and opts for cheap 3D character and enemy models, but Mind Zero has just enough atmosphere to achieve its basic goal of setting up a dark and gritty world.

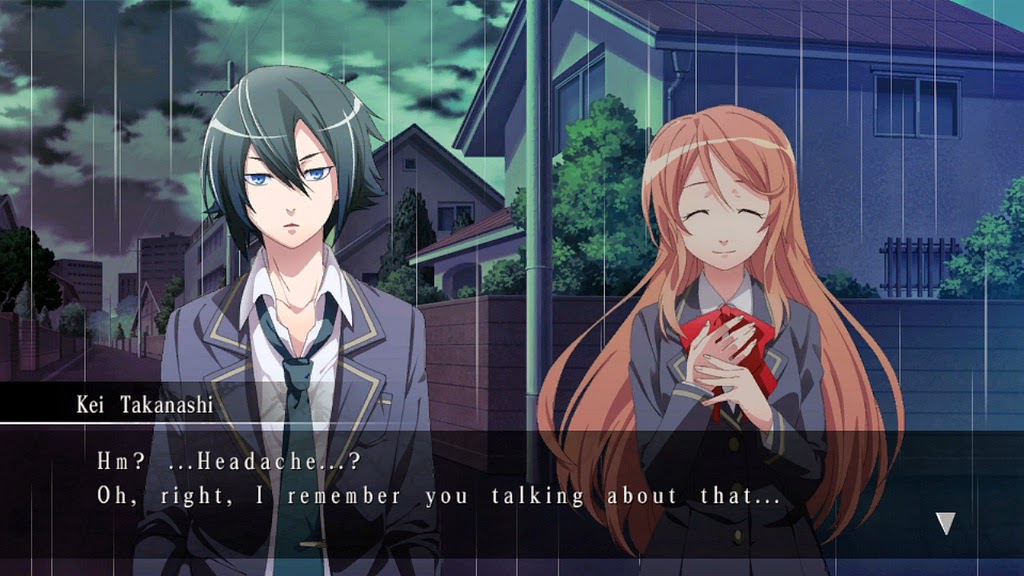

The game plays fine, in other words. The real problem with Mind Zero is that, while its concept and mechanics are both sound, it’s hampered by some really underdone scripting. Whereas in the Persona games players really come to care about the characters (Rise… <3), and every single line of dialogue seems to have a purpose, Mind Zero’s group of heroes suffer from characterisation inconsistencies and the dialogue isn’t paced especially well, with loads of stuff thrown in for what I think was designed to be characterisation, but in effect didn’t add anything to my understanding of the characters or the plot.

There’s numerous conversation arcs that are completely optional in the game, or alternatively yield side quests. I have got to admit that after around ten hours of play I started to avoid these completely, as they simply didn’t do anything for me. Contrast to Persona 4, where I was literally handing on every word delivered, and it speaks realms of the disparity between the quality of the storytelling between both games.

Because the narrative is so inconsistent, Mind Zero struggles to hold on to its themes. Philosophically it treads much of the same ground as its inspiration, touching on themes such as nihilism, self discovery, the value or importance of friendship and so on, but the lack of scripting focus means that the game never feels like it goes in as deep as the Persona games. The game also ends on a cliffhanger, which was clearly designed to leave an air of mystery for players, but comes off as being a sales pitch for a sequel.

It’s unfortunate that Mind Zero chose one of the greatest JRPG franchises to ape, because the core combat system is really quite entertaining and mechanically sound. It’s also unfortunate because for all my criticisms above, Mind Zero is still a very entertaining game, it’s just that when you deliberately compare yourself to the greatest, you’re inevitably going to disappoint. Were Mind Zero to stand with its own narrative drive, and free of the comparisons to Persona, this game would have appreciated for what it is, rather than what it is not.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld