Review by Matt S.

Review by Matt S.

Child of Light is a poem, both literally and figuratively. I resist to even call it a game; it simply stands as a testament to the true artistry that an interactive work can achieve when a developer is allowed to simply create. Clearly unburdened by commercial expectations (I have no difficulty in believing Ubisoft has very low sales expectations for this one compared to Watch_Dogs or Assassin’s Creed), but more so, unburdened of the need to create a game, the developers behind Child of Light have instead created something that transcends its peers and is really quite special.

Tonally I imagine the first few hours of Child of Light will feel unfamiliar and unique – if not uncomfortable – for most people. We’ve never had a game that reveals its story through verse, for instance, and this places a different kind of demand on the player’s attention than they might expect (especially for a game coming from a major publisher). We’ve never had a game where the characters talk in verse. And so, while the core narrative of Child of Light is quite simple (it’s a modern fairy tale of the journey of a girl who has fallen deathly ill to a fantasy realm where she needs to save everyone and everything from an evil queen), within that almost clichéd context the developers have been able to draw together a wide range of deeper themes and meaning from mere snippets of dialogue and threadbare cut scenes. Players with a more academic bent will genuinely be able to study this game for meaning, and I suspect that this, too, was a developer’s intention.

That’s not to say the game is all serious and intellectual, however. There are moments wordplay that are clever, witty, and even funny, but it’s a straightforward humour; when the dialogue is amusing it’s because it’s a play on the structure of poetry itself, rather than the words that are spoken. There is also an attention to detail throughout the world that builds levity as well; for instance, a town has had its people turned into crows through evil magic, and that’s a standard RPG trope. But in Child of Light the crows are drunk or smoking cigars, or otherwise behaving as human beings could be expected to behave should such an event happen to them. This sense of humour is subtle – almost too subtle for an entertainment industry where attempts at humour are more likely to produce Bulletstorm or Serious Sam – but I do hope those that play Child of Light appreciate the way humour is presented by it, because it is charming stuff.

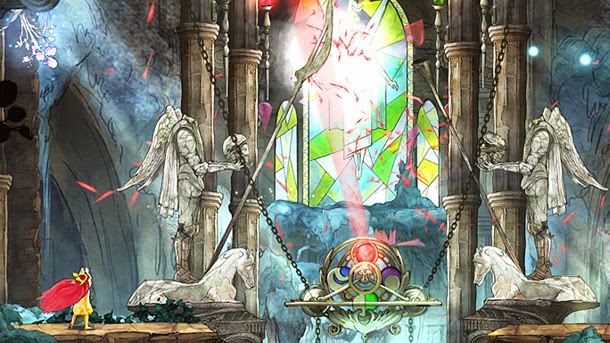

As the game progresses, the words spoken merge with the lavish art work and character design to create an ethereal beauty; a dreamlike innocence that might be threatened by something dark, but it’s never wholly replaced by it. I’ve seen people compare this game to the narrative structures of other popular fairy tales, such as the works of the Brothers Grimm, but I find that a poor comparison that fails to understand the subtle differences in tone. The Brothers Grimm fairy tales exist within a world of darkness that tries to swallow innocence. Child of Light is more like the classic Neverending Story film; it’s a tale of true innocence holding back a threat of darkness.

The poetic nature of the dialogue quickly lends the game a soft, but perceptible rhythm. Players float (literally) from one chapter to the next, and it happens quickly, without ever really getting bogged down by excessive difficulty spikes or mind-bending puzzles. In the background, a truly elegant soundtrack from Canadian singer/ songwriter, Cœur de Pirate, effortlessly melds into this rhythm, and supports it by encouraging players to move in concert with it. Players will never feel rushed, but nonetheless the game’s sense of pace is near-perfect and scenes roll by with just enough regularity to maintain a sensation of flow without creating “blink and you miss it” moments. Like a good poem, players become invested enough in the experience that they can feel its emotion, but they’re also never stuck re-reading the same passage over and over again in order to understand it.

The world of Child of Light is also one of childlike wonder. Early on players are restricted to moving around on the ground. This serves as a tutorial (without ever feeling like a tutorial or being removed from the context of the rest of the adventure), and while it feels restricted, these early moments equip players with the basic understanding on how the adventure will work. Following the first major highlight (a boss battle), players acquire the ability of flight, and that’s when Child of Light’s creativity is let loose. Without ever giving players the opportunity to get lost, Child of Light never really limits the player’s ability to engage the flight ability, and the environments are filled with interesting things to see and do, both vertically and on the ground. A lesser game would restrict the flight ability to specific moments and force players to use more mundane abilities to solve its other challenges, but with few exceptions Child of Light works around the power of flight, not despite it.

It takes confidence to give players a skill as powerful as flight in a platformer, as it immediately renders so many of the traditional challenges of the genre redundant. Imagine if Mario had a permanent ability to fly in his games – there wouldn’t be much of a game left. It’s testament to the skill of the game’s developers that they’ve managed to build a game that still offers challenge when players have the uninhibited ability to fly around.

What lessens the game somewhat is the combat. If you had have put Child of Light’s combat in another other RPG or JRPG, I would be a very happy person. Very similar to the Super Nintendo and PlayStation One Final Fantasy games, Child of Light’s combat is turn based, but plays out in real time. A bar at the bottom of the screen shows the order in which attacks will play out, and characters and monsters can use various abilities to either hasten their own attacks, or slow down the attacks of their opponents. It’s a simple but elegant system that does manage to offer some challenge.

The enemies are an interesting bunch too, drawn from a range of fairy tale mythologies. Beautifully drawn and offering plenty of personality, there’s no real hint to an enemy’s weaknesses until you’ve done some experimentation, which means that each new monster brings with it a new sense of discovery and even wonder as you probe to see which elemental attacks or special abilities they might be weak to. Mechanically it’s a very old-school approach to combat design, but within the theme of this specific game, it works and even feels modern.

So why would I say that I find it disappointing, then? While I don’t think the developers could have done a better job in making the combat fit the theme, I wonder whether it needs combat at all. Yes it adds a sense of danger to an otherwise serene adventure, but if I’m being entirely cynical I would argue that the combat of Child of Light is there in order to give Ubisoft a marketable feature within the game. Or in other words, precious few would buy “a puzzle platformer with a narrative told in verse.” Plenty, however, would be interested in “an artsy RPG.” Both describe Child of Light, but one suspects that if the developers could have done away with any feature in the game, or were forced by management to implement something, it’s the combat system. It’s there, it works, it fits with the theme of the game, but it still feels like an afterthought.

I’m not going to dock points off the game’s score though, because to me Child of Light represents everything that arthouse games can be, or should be. This game also represents the reason why major publishers should dedicate some of its annual budget to greenlight something truly innovative. An indie developer couldn’t create Child of Light. No other major publisher would greenlight it, so kudos to Ubisoft for taking the risk.

Laden with meaning (and in future articles on Digitally Downloaded I’ll be writing plenty more about that meaning in the weeks, if not years to come, I suspect), this game uses poetry as its basis and executes on that vision so well that it is, effectively, interactive poetry.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld