Last week in Europe and Australia, Capcom released Resident Evil: Director’s Cut on the PlayStation Network as a PSOne Classic release.

On the surface, you wouldn’t expect this game to be worth the premium price Capcom is asking for it – after all, games have come a long way since the PlayStation One. Developers can now render high-definition creatures of the night, dynamic lighting, and surround sound. How can this game possibly be worth playing if it’s not even slightly scary?

|

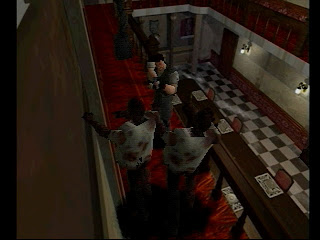

| The static camera was used so effectively in this game, it’s still impressive |

|

| Moving slowly and turning even more slowly makes it easier to die… and that’s not necessarily a bad thing for horror |

nice

Thanks! 😀