Article by Matt S.

You can learn a lot about a culture from the games that it plays. I’m not just talking about video games here (though, obviously, I’m a big advocate for Japanese video games as well), but rather the traditional board and card games that predate video games.

Through a culture’s games, you learn something about everything from the aesthetics and design principles of the culture, through to view on the world – remember, toys and games act as a teaching tool for children, so it makes sense that those objects would also be representative of the culture that created them.

Many of Japan’s traditional board and card games are not particularly well known outside of Japan, so I thought I’d do a short introduction to some of the must-plays for anyone interested in Japan, and keen to learn a little more about the country through these artefacts.

Shogi

Starting at the most obvious place, shogi is “Japanese chess”, and on a superficial level the two games are ideed similar. Your job is to capture your opponent’s king, using pieces that arrayed on the board just as chess pieces are, with many of the pieces sharing the same way of moving around the board.

There are, however, significant differences, and indeed, the process of unlearning chess to understand how to move pieces around the shogi board, and the strategies that you need to apply is a truly annoying learning curve for people who have played enough chess to have preferred strategies within that game. For one thing, in shogi, pieces can come back on the board once captured, meaning you can turn your opponent’s pieces against them. Additionally, pieces get “promoted” much like in checkers when they reach the other end of the board, meaning that movement around the board is more fluid than in chess, where for much of the game both sides are trying to thrust in one direction.

Shogi reflects many of the strategy and tactics that the samurai would use on the battlefield, and indeed, the “capital” of shogi, Tendo, became that way because the town was impoverished, and the local samurai turned to carving shogi pieces, as one of the few things they could do with honour, because shogi was so closely linked to the samurai (incidentally, Tendo has a shogi museum and is a must-visit for any fan of the game).

Hanafuda

Hanafuda is a relatively well-known game among video game fans in the west, because Nintendo was famously involved in the manufacture of the cards before becoming the video game giant that it is today (you can still buy Nintendo-manufactured hanafuda cards to this date, though that is a very small part of Nintendo’s business now).

Hanafuda is effectively a little like poker, in that it’s a card game in which luck, and gambling against your luck plays a massive role. Your task in the dominant form of Hanafuda – Koi Koi – is to form “sets” of cards, as cards are drawn and placed on a common pool. Once you form a set, you’re able to risk playing on, to get more sets and points, but if your opponent completes a set before you’re able to form the next set, they get a whole boatload of bonus points.

Interestingly, there are a lot of people in Japan that go without ever learning how to play Koi Koi, as the game had a similar reputation that poker once did in the west. The links to organised crime (in this case, the yakuza), meant it was a game with a bit of a “dirty” reputation. These days it’s less of an issue, of course, but between Hanafuda and the love hotels that Nintendo once owned, you get the sense that everyone’s favourite company of family-friendly games used to have its share of sordid business interests.

Hyakunin Isshu

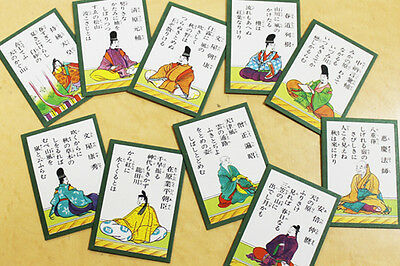

Hyakunin Isshu is a rather clever way that the Japanese have been able to convince their kids to learn something about classical poetry. We’re talking about really old poetry here – from around the 10th century. The game is somewhat surprisingly popular to western eyes, based on its simplicity as a game, but like with spelling bees and similar, it’s a good way to learn and demonstrate aptitude towards a particular field of learning that’s important to the culture.

In Hyakunin Isshu there are two decks of cards. One set of cards, containing sections of poetry, are arrayed out on the ground (never a table) like a game of memory (only with the cards being face up rather than down). From the other deck of cards, a reader will draw one card and start reading the poem. The players compete to find the card on the ground, and grab it before the opponent.

The cards on the ground only contain the last little passage from the card being read out, so the skill to this game is knowing which poem is being read before the reader actually gets to the passage printed on the table cards. Naturally, the very best players of this game have memorised a volume’s worth of classical Japanese poetry, making this a truly noble game to play indeed. The poems themselves are gorgeous, whether you actually play the game or not, and the good news is that there is an English translation, for people that don’t want to learn the entire language to appreciate this game.

Hanetsuki

More “sport” than board or card game, but it’s hardly something you’re going to see played to Olympic standard, Hanetsuki is basically badminton, but without the net. Two players compete by hitting a shuttlecock back and forth, and trying not to let the shuttlecock hit the ground.

The longer the shuttlecock is in the air, the greater protection that it’s meant to provide the players from mosquitoes in the coming year. The loser of the game gets marked on the face with India ink.

If this sounds more like a tradition than a proper sport, then you’d be right. Hanetsuki is played principally as a New Year’s Festival tradition, and is played by girls (though of course boys are most welcome to join in the fun as well). It’s a cultural tradition rather than a competitive game, and the paddles that you can buy to play often have the most gorgeous designs printed on them.

Sugoroku

Sugoroku is interesting, because there are two different “versions” of the game, but they are wildly different in how they are actually played. E-sugoroku is not “electronic sugoroku” as you might guess from the name. It’s basically snakes and ladders, in which players move their pieces around an illustrated map. Historically, that map would feature Buddhist writings and teachings on each space, but that’s rather dull, so by the Edo period, players were instead enjoying a trip across the Tokaido (the road that linked Tokyo and Kyoto, and is every bit as scenic of a journey as it sounds).

|

| E-sugoruku |

The “real” sugoroku is ban-sugoruku, and it came to Japan via the silk road in around the seventh century. Over time it became a cultural property of Japan, and a game that the nobility generally enjoyed in their idleness. It is incredibly similar to backgammon (and indeed the reason that it’s barely played today is that most people would rather just play backgammon).

|

| Ban-sugoruku |

Ban-sugoroku went through a period of being outright banned in Japan, and speaks to the lifestyle of the Japanese from a very long time ago. E-sugoroku takes players on a trip through either landscapes that have inspired Japanese artists for generations (the Tokaido road version), or Buddhist teachings, which has obviously been critical to the spiritual and intellectual development of the Japanese culture for millennia.

Kendama

Kendama translates as “sword and ball”, and it’s a skill-based toy that tests the player’s hand-eye co-ordination. There’s a ball that’s attached to a string, and a paddle that has three “cups” (one on each side, and one at the end of the device), and a “spike” which the ball can land on, courtesy of the ball having a hole driven into it. The goal of kendama is no different to any other cup-and-ball game; you want to land the ball on one of the four potential landing spots.

Kendama isn’t native to Japan – it came to the country via Nagasaki, back when Nagasaki was the only port open for trade with foreigners. The novelty of it caught on quickly, though, and these days there are organised competitions held around kendama across the country, and your performance actually gives you kyu and dan rankings, not unlike a martial art. That should tell you what the Japanese think of the game – it rewards focus, discipline, and control, and that very much speaks to traits that the Japanese hold particular respect for.

These days kendama are available everywhere, and are quite cheap. I own one, though kendama demands a form of hand-eye co-ordination that I have no patience for. It might actually be a useful tool for e-sports athletes to train with, however, as much of the control required to master the toy is twitch control.

The Japanese love plenty of other traditional games, of course. Go and Mahjong are popular in Japan, and tend to show up in the likes of Yakuza and other games to depict Japanese culture. I’ve deliberately left these out as, unlike Kendama or Sugoroku, they were never “naturalised” in Japan and remain definable as games from China. That being said, you should absolutely try both of those games too, as they are incredibly powerful cultural products in their own right.

Have you played any of these games? Have a favourite? Be sure to let us know in the comments!

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld

Please help keep DDNet running:

Become a Patreon!