Review by Matt S.

Dragon Sinker isn’t exactly subtle about its inspirations. It’s so slavishly loyal to the early era Dragon Quest titles that it may as well be a fan-made project. Yet, while it is mechanically very similar to the source of its inspiration, it’s also a game that wildly misunderstands what made those original Dragon Quest games so wonderful, and so enduring to this day. As a result, Dragon Sinker is a pale, poor imitation, and while you can derive some grindy fun out of it, you’ll forget about your time spent with this almost as soon as you stop playing.

When you think over the early Dragon Quest games, what are some of the things that you’ll immediately recall? One is, surely, the art. Akira Toriyama’s character and monster designs were so brilliant that they’ve become every bit as iconic as the art we see in games like Pac-Man and Space Invaders. The slime, in particular, has become so iconic that it’s one of the de facto symbols of today’s Square Enix itself. I know my house is filled with Slime character goods.

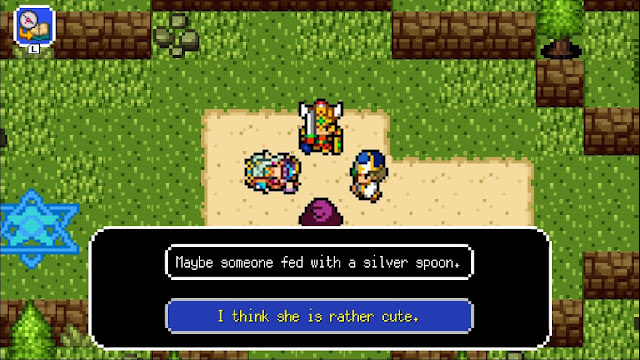

Dragon Sinker has some mild differences to Dragon Quest. Combat happens from a side-on perspective, more like Final Fantasy, than Dragon Quest’s first person view. But make no mistake, from the overworld to the structure of the character models, this is a game that was made by people who wanted to make a Dragon Quest title. Sadly for them, Dragon Sinker’s art is about as far from “distinctive” or “interesting” that you could imagine. There’s an incredibly limited number of enemy designs, with “palette swapping” becoming an issue almost immediately. For people who are less familiar with older JRPGs, palette swapping was a thing that game developers used to do to use the same enemy design a couple of times, and save themselves the need to produce as much art (and, often, save space on the incredibly limited cartridges). So, for example, in Dragon Quest, the first slime enemy is blue. Later on you’ll run into a more powerful orange one. It had the exact same design, but because it was coloured differently, players knew that it was a different enemy.

Of course, if you’re too over-eager with the palette swapping, players are left with the impression that they’re playing a lazily developed game. Those earlier Dragon Quest games straddled the line perfectly, and, for the most part, the base character designs were so vivid, charming, and enjoyable, that it was hardly seen as an imposition by the players when there was some palette swapping going on. Fast forward to Dragon Sinker, and the story’s very different. Palette swapping is so frequent that it does indeed appear like a lazy effort by the designers, and the enemy designs are so painfully bland that looking at them once was an imposition on the players, let alone asking them to look at the same enemies over and over again, coloured slightly differently each time.

The music of the Dragon Quest series has also been a consistent highlight through the years. From the opening fanfare through to the little level up ditty, there aren’t many JRPG fans that won’t get a warm sense of immediate familiarity when hearing the music from a Dragon Quest game. Now, with Dragon Sinker’s music… I actually can’t remember it. I last played the game just a day before I sat down to write this review and… I don’t remember the music.

What Dragon Sinker does understand is that early JRPGs were all about an incessant grind. You’ll need to run around in circles fighting an unending number of random battles to level your heroes up, and then, once you’re powerful enough, delve into a dungeon, where you get to fight a boss monster. Do this over and over again until you’ve defeated the final boss and it’s game over. While this approach to gameplay will seem aggravating by modern standards (because if you set the difficulty to the higher settings, you are in for a lot of grinding), in fairness to the developers, this is an accurate emulation of how games were made back then to pad out their length and make the adventure feel like an epic undertaking. I can’t begrudge the developers for Dragon Sinker’s combat system, but I say that with the disclaimer that to this day I play the original Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest through at least once per year.

What is less forgivable is the interface. Menu navigation for special abilities and the like becomes an arduous process of cycling through page after page of abilities to try and find the one that you want to use. Given that you can make your way through the game only using a couple of abilities, there was no reason for the developer to give each character so many of them, making the menu system in combat so cumbersome.

In fact, the game shoots itself in the foot by making characters so versatile. One of the key gameplay features is the job system, and the ability to build up multiple parties of heroes to take into combat. There’s little point to play with the job system, because each character ends up with such a range of abilities just by levelling up that “customisation” is more a case of useless time wasting than a rewarding system. Additionally, you can only have four characters in battle at once, but can swap between a number of four-hero parties on the fly during combat. The purpose of this was to make players be strategic in their party construction, to try and make sure that each “unit” was able to tackle a range of different challenges, but aside from swapping a party out when they were running low on health or magic power during boss battles, there was never any point in engaging with this system, either.

We’ve seen other retro-themed JRPGs do a great job in working within the limits of the retro form to tell interesting and even emotionally resonant stories. The Longest Five Minutes was only released a couple of weeks ago, and it’s one of the finest games we’ve seen to appropriate that retro style within a modern context. So it can be done, and it can be done in new and interesting ways. But Dragon Sinker goes the other way. It’s so dedicated in its goal to stay traditional that there’s not a moment in the game that exhibits any creativity of its own. The storytelling is competently bland, and doesn’t do much more than push you from one location to the next. There’s a bit of a sub-story in there with elves, humans and dwarves not much liking one another, before banding together to put down an existential threat to them all, but that plot angle got dull a very long time ago, and this game doesn’t put a new spin on it.

The game also has Kemco’s aggravating approach to side quests; generally speaking, once you’ve cleared a dungeon and defeated the boss as part of the main storyline, you’ll head back to the town to close off the quest, and there you’ll run into someone who, as a side quest, needs you to go back into that dungeon. It’s the most irritating, artificial way of stretching the length of the game by forcing players to backtrack, and this game, as with all Kemco JRPGs, turns it into such a formula that it makes me want to hurt my game console.

Dragon Sinker’s strength is that, in being such a slavish homage to one of the greatest JRPGs ever made, it too manages to be more playable than many of the original story JRPGs that Kemco produces. It is an endlessly replayable formula that the developers are copying wholesale, after all. But then, in being a slavish homage, the Dragon Sinker also opens itself up to comparisons with the game it’s derivative of. And, sadly, it doesn’t come out well in those comparisons at all.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld

|

| Please Support Me On Patreon!

|