Review by Matt S.

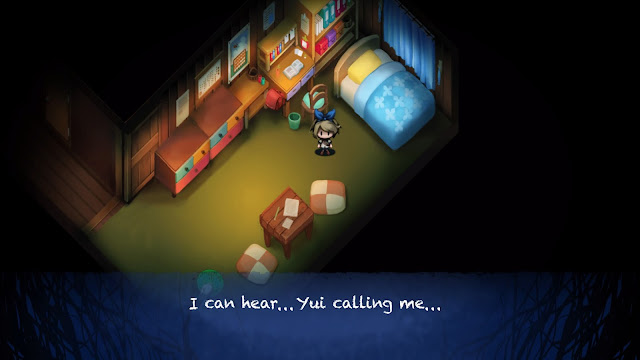

Yomawari: Night Alone was one of those games that has really stuck with me since I first played it a year ago. The game itself doesn’t look like it should be something special; it has a beautiful (albeit simple) art style inspired by classical Japanese painting techniques, but then there are a lot of beautiful, indie games that make use of 2D art inspired by one art movement or another. That’s not enough in itself for a game to stand out.

Related reading: Matt’s review of the original Yomawari.

More significantly, as beautiful as it is, it looks both cute and silly. Sure there are monsters, but they look like colourful nonsense, and the ultra-chibi 2D sprite that represented your character looked like she could have belonged to a ultra-cute JRPG aimed at kids. I went in thinking for a horror game, there’s no way that Yomawari could actually be horrifying, right?

Wow was I wrong. Yomawari has stuck with me over the past year because it’s a game that’s absolutely terrifying under that surface of its. It’s not overly gruesome, there’s no intense combat scenes (or combat at all), and the pacing of the game was quite sedate for the most part, but what would have been weaknesses in any other horror game were spin into fundamental strengths of a game that combined its art with minimalist storytelling to build a narrative that was rich with atmosphere and ripe with Japan’s very distinctive sense of horror. Yes, something like The Evil Within 2 will be more effective in terms of immediate thrills and its visceral depictions of monstrosities, decapitations and gore, but Yomawari: Midnight Shadows more subtle chills makes it the better and more meaningful game, and the one that you should have on the top of your Halloween “to do” list this year.

Rather than go through much of the theoretical detail again, I’ll recommend that you read my review of that original Yomawari, which does go into some significant depth about where the artistic and thematic influences of the fledgling series come from. Midnight Shadows comes from much the same place, and indeed, to get the bugbear out in the open from the start: it’s a little too much like its predecessor at times, and that deadens its ability to outright shock a little. Without going into spoilers, in the opening scene of Night Alone something absolutely mortifying happens, and it comes out of nowhere. When it happened to me the first time my eyes were pulled wide, and I was left staring at the screen for more than a few seconds. It was less outright horrific than it was deeply saddening, but it was genuinely shocking, and sets the tone for the game. Midnight Shadows pulls almost exactly the same kind of trick for its opener, and while being a good way to remind me that I should be mentally preparing myself (“yep, buckle down, you’re playing a Yomawari game,”) there wasn’t the same raw shock this time, which made the opening less immediately compelling.

That being said, as you push further in, the narrative still manages to surprise and hit you with the kind of awe that only the finest horror tales can achieve, because Midnight Shadows tells a very different story to its predecessor in the very few words that it uses, and by the end it’s just as provocative. This time around you play as two little girls, who are closest of close friends, but one evening, while watching a summer festival, one of them tells her friend that she’s moving away the next day, and they’ll likely not see one another again. On the way home from the festival, the two girls are separated and, both deeply worried, they try to find each other, even as the many deadly spirits the town plays host to come out in the dark for their time in the open air.

There’s an intense feeling of loneliness as, either as one girl or the other, you slowly clop your way around town, following the scraps of clues that each leaves. The small country town where the game is set is silent, with not another living soul to be seen, and the echo of each girl’s feet on the pavement, coupled with the sound of locusts that are so emblematic of a Japanese summer, create a soundscape of pure isolation and smallness. Your character isn’t fast, she’s unable to fight back, and the way the game keeps finding subtle ways to reinforce just how alone she is is really quite affecting.

What really drives that theme home, however, is the spirits themselves. As mentioned, the town has an abundance of ghostly figures of all shapes and designs. Many of them are actively hostile and try and chase your character down on sight. But many of them are not. Many of the spirits seem to be going through the motions that normal people do when out and about in town; a child-like ghost chases a ball bouncing across a road. A spirit in a wheel hurtles down the road as though driving somewhere. Touch these creatures and it’s game over, but leaven them alone and they’ll ignore you it turn.

Soon enough it starts to feel like, as the only living being in a playground for ghosts, you outright don’t belong. That as much as the day is for the humans out and about in town, come nightfall it’s the spirit’s turn, and with your presence you’re disrupting their orders of things. As the outsider it is, again, really difficult to feel anything by an overwhelming loneliness, and this atmosphere permeates the entire Yomawari experience.

That loneliness also comes with another overwhelming sense; one of sadness, and if you were to try and pin down the one most significant difference between Japanese horror, and a more western sense of horror, it’s just that. Japanese horror is both sad and tragic. Western horror, be that through films, books or games, tends to hone in on the power of a creature, monster or being that’s trying to hurt the protagonist or protagonists. These killers are usually ugly, often “insane”, and seem to take pleasure in the killing. There are of course exceptions to the rule, but from slashers to zombie films, Exorcist through Saw and Hostel, the fundamental horror in these works is found in the violence inflicted on the victims.

Japanese horror is generally different. The victims still end up dead, but through the course of the work, we’re encouraged to feel as strongly sympathetic for the “monster” as we are the victim. From the ghosts that die under the most tragic circumstances in Ju-On or The Ring, through to games like Project Zero and Silent Hill, which generally spin around some great tragedy that happened in the area that the protagonist is trapped within, the horror for the audience is found in the tragedy and the circumstances that turned these creatures into killers.

Yomawari belongs to that tradition. Mechanically you can’t fight the enemies, or even run away from them particularly well. Your goal through the game is to simply navigate past them, but however ugly or dangerous some of the enemies are, none of that’s the point. Rather, the game’s atmosphere and horror comes from the isolation and fundamental tragedy of these two inseparable friends being separated, and the panic of not knowing what’s happening to the other. In other words, Yomawari aims to build horror through players being empathetic and sympathetic rather than outright revolted.

In that context the super cute characters and ukiyo-e style art really works to the game’s benefit. As I mentioned before, Yomawari is a game of few words, and fewer still cut scenes. It’s in being immersed within the art, and coming across ever more creative and twisted spirits that the game draws its atmosphere and narrative. It’s in that feeling that you really shouldn’t be heading down a darkened alley at night with nought but a torch with you. It’s in simple tricks with that light, which only shows what’s going on in front of you. Sometimes a spirit will hit your character from behind without you even knowing what’s going on, and as frustrating as that can be because it’s an instant life lost, checkpoints are frequent enough and the unknowingness about it all certainly helps build tension regarding what you can’t see on the screen.

Yomawari doesn’t even try to be much of a game. Working out how to navigate around various spirits provides the limits of its “gameplay,” and these are ridiculously easy puzzles for the most part (though the closing chapters might frustrate some). Occasionally you’ll need to use one object or another as part of the puzzle solving process, but the game never quite manages to get all the way into adventure game territory. There are moments of stalker horror, where the girls can hide from the spirits by ducking into a bush, behind a big sign, or similar. Unlike most stalker horror games there’s absolutely no risk of being discovered once hiding, which reduces the tension of hiding a little, but this game isn’t really about that. It’s a good length game, and again, Yomawari is all about the clean, minimalist storytelling and the atmosphere. There are some charms you can pick up along the way which give your character some slight bonuses: for example, the ability to hold more pebbles to throw, or the ability to run for longer. These don’t add much the the experience, it’s got to be said, and yet I was so engrossed within the game that this is one of those rare times in a game that I simply had to collect them all.

For the most part, the challenge of Yomawari is simply finding your way around a town that, by night, is so much more terrifying that it would ever by by day. You’ll be directed to follow a clue to your friend that she might be at a library, but every major street you look to take has one apparition or another blocking your way. Weaving around back alleys, listening carefully for the “thudding” of the girl’s heartbeat that indicates a monster is nearby, and slowly exploring the town is more than enough interaction for what Yomawari wants you to experience. Indeed, the subtitle: Midnight Shadows, sounds odd at first, but if you’ve got an understanding of how Japanese architecture and city design works, nighttime does throw up a lot of shadows from buildings pushed so closely together, roads to narrow in design, and gap after gap under vending machine, around statues, and under houses. By day it can be a delight finding all these hidden spaces – something Yokai Watch has been so effective in tapping into. By night, the layers of darkness on top of one another can be intimidating if you’re somewhere unfamiliar.

It has its moments of shock, too. I might have been slightly desensitised to Yomawari’s tempo and pacing with those shocks thanks to having played the predecessor, but the game still has a way of burrowing into my consciousness quite unlike any other horror game I’ve played in recent years (aside from the indomitable Corpse Party, of course). Yomawari: Midnight Shadows looks like a game that would be easy to make. But telling a horror story this effectively with so few words takes a mastery of the genre that very, very few possess.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld

|

| Please Support Me On Patreon!

|