Review by Matt S.

At the height of his powers as a filmmaker and storyteller, Tim Burton had such a mastery over the juxtaposition of innocence and the macabre that his films had a tone all of their own. He loved dropping the gothic on suburban America, and loved making the physically ugly contrast with the purity of soul. Whether it was Edward Scissorhands, Beetlejuice, or the characters of Corpse Bride, there was a constant and overt initiative throughout his films to show how we – normal people – are the ugly ones, for the way that we treat the “other” in society.

Burton found suburbia, with all its façade as a utopic American dream, to be stifling and deeply frustrating. He hated the experience of growing up in the suburbs, it grated on him, and much of his creative vision was informed by the abstract horror that this kind of “normalcy” subjected him to. Little Nightmares, a new puzzle/horror video game, takes an aesthetic that is effortlessly “Burtonian” in tone, and while it doesn’t have that same overt social commentary, as a study in atmosphere it’s an intense and deeply rewarding experience.

The everyday world of adults is the grotesque in Little Nightmares. Your avatar is a personification of innocence; a wiry, feeble little girl (it’s a girl, though she’s wearing a yellow raincoat that makes it hard to tell what she is at all, and that’s part of the mystery of it), thrust into a nightmare world where scales are huge and everything is just out of reach; switches need platforms to reach, and sprinting across a room to get to a door before a timer ticks down is an intense race against the clock. Spaces are elongated and menacing; like in the classic film The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, the way the simple architecture – built for adults as it is – bears down on our little avatar is intimidating and claustrophobic, so that even the most mundane and simple suddenly start to feel threatening.

— Matt @ DDNet (@DigitallyDownld) May 1, 2017

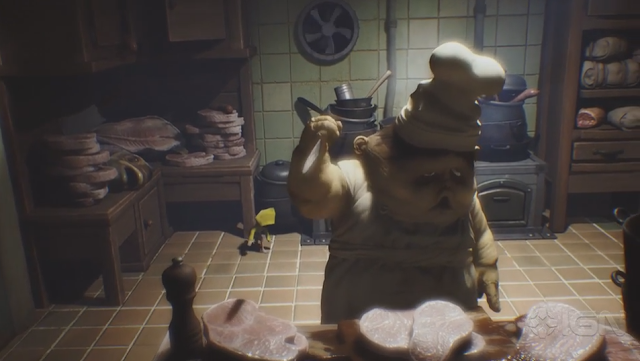

The real threat are the adults themselves: twisted, violent monsters who hunt our little protagonist down for reasons we are (initially) not sure of at all. These adults are misshapen representations of the most normal of normal people; a janitor with terrifyingly elongated arms barges into a nursery at the slightest hint of a disturbance to… his wards, perhaps? Again, it’s a bit of a mystery, but you’re definitely in a nursery, and the avatar’s entrance, carrying a small lighter in his hand, certainly seems like a disturbance. Later, a disgustingly bloated chef with bulbous fingers looks at the avatar as an additional bit of flavour for the stew he’s got bubbling along. If these creatures spot you, you’ll need to run and hide from them. Fighting back is not an option, as they are faster and stronger than you are. Mechanically, these moments in the game work as stealth sequences, where the avatar needs to read the patterns of the beast’s movements to tiptoe past it without being spotted. More than just an effective mechanic, however, these sequences really ram home the fragility of innocence in Little Nightmare’s twisted universe.

While the game itself isn’t overly long (I had it clocked in seven hours, and most would do it far more quickly), the narrative is gripping throughout, and it all goes into some very dark rabbit holes that I don’t want to give away up front. Predominantly, the game works as a mystery, as the early going is very stingy with any kind of concrete information, but I promise you, by the end of the game you won’t be feeling like it’s all one giant tease. The revelations have impact, and are worth mulling over (perhaps with a glass of fine wine or two) after you’re done.

When not avoiding these monsters, the little avatar needs to work his/her way from one room to the next, invariably solving a puzzle that will open the door to the next room. The puzzles tend to be minimalist and aren’t overly layered; the game especially likes the “this switch is just out of your reach” trope. Figuring out the solutions to these puzzles can be maddening, not because they’re particularly difficult (you’ll know what you need to do each time almost instantly), but rather because there’s only one solution programmed into each puzzle. Or to put it another way, when a room might have two boxes of nearly exactly the same design, the game will only allow you to drag one of those boxes to use it as a ledge to reach a previously unassailable spot. At other times objects that looked like I should have been able to interact with them couldn’t be interacted with at all, and vice versa; I don’t know how long I spent stuck in one tiny room at one point, getting incredibly frustrated, because a wooden board that I needed to pull off a door in order to create an opening didn’t look like it was something that my character could grab onto.

I’m all for difficult puzzles, and I appreciate that the developer didn’t want to use inelegant solutions like highlighting interactive objects with an artificial colour or glow. That would have interfered too much with the consistency of the game’s visual design, which is so important to Little Nightmares’ atmosphere. But by the same token game developers need to be careful that they don’t look like they’re trying to trick players with obtuseness. If a team creates an environment that looks like it should have multiple solutions to a puzzle, players need to be able to complete the puzzle using any of those possible solutions. If you’re going to have interactive and non-interactive objects, critical to puzzles, sharing the same space, differentiating the interactive from the non-interactive is a really important element of design.

I also found navigating around the world to be a pain at times, and this is perhaps a consequence of the striking side-on perspective and art direction. There was the odd moment where what seemed like the path forward wasn’t, and I would waste a good deal of time trying to “solve” a puzzle that didn’t exist. At other moments the way forward wasn’t evident at all, until I discovered by accident a space I could squeeze through after, again, wandering around in frustration for a while.

These irritations aren’t enough to actually dampen the experience of Little Nightmares, and the overall game is kept to a nice, sharp length, so you’ll feel like you’re making rapid progress even during those times when you’re floundering around a bit. And, to a certain extent, the helplessness that you’ll feel from time to time, particularly when you’re trying to solve puzzles with a hulking monster breathing down your neck, works in nicely with the game’s overall tone. I’m sure the developers could have done it better, but the consistency across the experience in Little Nightmares is, nonetheless, the game’s strongest feature.

It has been a long time since Tim Burton has created a truly classic film, and much of his modern output reflects a man who has mellowed; he no longer sees the macabre in the mundane, and he’s quite content making cheerful little dark comedies or fantasies like that Alice in Wonderland film. If young Burton was to make a game, I’d like to think it would have turned out like Little Nightmares. It might not be the most refined experience (something young Burton’s films were often guilty of as well), but that vision, and the rare mastery over a horror many of us feel but struggle to articulate, makes this game frequently surprising, intense, and always sublime.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld