Review by Matt S.

I suspect that many people, when they first sit down to Neo Atlas 1469, will find themselves quite confused with regards to what, exactly, the game is meant to be. It looks like it wants to be a narrative-heavy game about admirals sailing the seas. Then it shifts gears and starts to instruct you on how to set up trading routes to earn your company money.

Related reading: Also from Artdink is A-Train on the Nintendo 3DS game. It’s incredible. Matt’s review.

You start to get into that … and then the game will shift tone again. The truth is that Neo Atlas is neither of the two things it first appears to be. In reality it is a cartography exploration game in which you need to journey around the world, discovering continents, people, and wealth along the way. There’s nothing else quite like it out there, and taken as an incredibly casual experience, it’s actually quite wonderful.

Developed by Artdink, the same simulation specialist behind the excellent A-Train series, in Neo Atlas you start out with a single admiral, a tiny fleet, and access to Europe and North Africa. You’re told to take what resources you have and have your fleet find its way around the world to eventually discover Zipangu (Japan). To do that, in the 30 years of game time you’re allocated, you’ll need to establish some trading routes between various cities in order to raise capital, which you can use to pay for a growing fleet of ships and stable of admirals, and then direct them to travel in various directions around the world. As you explore, you’ll find more exotic treasures that, once linked in trade routes, earn greater income for your company; but there’s also the increased risk of pirates or sea monsters making these trade routes dangerous.

Trade routes are simplified to the bare minimum: simply link two cities and the trading happens automatically. You don’t really need to worry about supply and demand, commodity prices remain steady, and you can’t form complex networks of trade routes; it’s always between two individual cities. Indeed, once you’ve set up those trade routes, you’ll largely forget about them, unless circumstances have rendered them unprofitable, at which point you’ll just drop them.

It’s the exploration where the real experience is found, and it throws up some surprises along the way. While the initial revealed map of Europe and north Africa remains the same in each game, the rest of the planet will be randomised each time. Africa might be roughly normal shape in one game, only for it to be an archipelago of small islands in the next. In the following game you might have a devil of a time sailing around at all, thanks to the extensive landmass across the planet.

This randomised geography ensures that exploration of the world is always a surprise and, just like the explorers of old, actually working out how to discover new land and chart around it is an exciting process. There’s no real penalty for running ships into land. Instead, their exploration is cut short and they’ll return to the nearest town, at which point you can issue new orders, but the time lost is just enough of a deterrent to make you want to try and accurately plot around where land will likely be.

When not exploring the oceans, there are also missions to complete. These are generally matters of simply directing a fleet to take an item to a certain area (or just show up at the area), but it’s a little trickier than that, as you’ll need to discover the area first. By default the game’s perspective is zoomed out to the point where you can spot major landmarks, like large cities, but to spot smaller villages or landmarks, you’ll need to zoom the camera in quite closely and eyeball around. You’ll generally get clues for finding important landmarks, so there’s nothing too strenuous involved in completing these missions, but they do add variety to the game, and help to develop the characters via brief story sections. Though the story is incredibly light and breezy, it’s nonetheless entertaining and works in the context of a game that’s designed, really, to be played while you’re watching TV or during a lunch break at work.

The lack of complexity transfers right through to the combat; when you send a fleet to do battle with a kraken or a pirate fleet, the game’s engine simply compares the two combat statistics, and the winner is the one with the higher rating. The best way to boost your combat power is to find treasure chests around the world that allow you to unlock more powerful ships in a basic skill tree. It’s the most “gamey” that Neo Atlas ever really gets, and it’s hardly what you’d call “complex”, but again this game has been designed as something to play in the background.

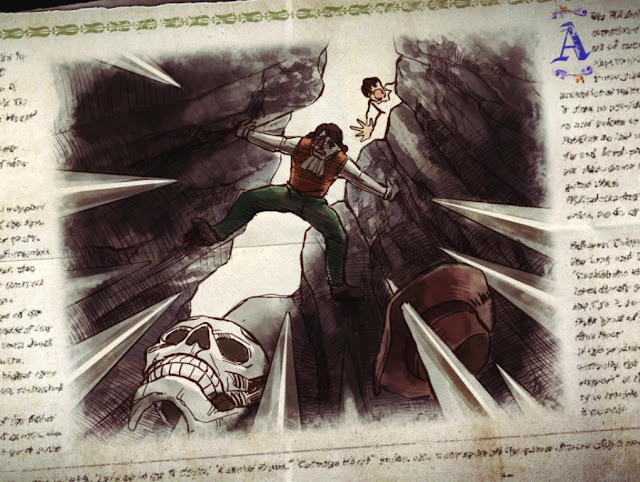

The itch that the game scratches remarkably well is the simple joy of cartography. As a kid, (when most other kids had posters of musicians they had a thing for), I had these lovely framed pictures of old cartography maps, and I loved imagining how these lands were discovered and drawn. Simple as it is, Neo Atlas is a game that recreates that experience. It may well be the only one that does so.

It’s also a ridiculously charming game with a lovely use of colour and cute icons to represent the various points of history across the world. I would’ve liked it if there was a better integration of history into the world; but I guess that’s a consequence of the randomised nature of the maps. Where you’ll get properly-named cities and artefacts throughout Europe to discover, once the map starts expanding it’s filled with random (and quite nonsensical) names for towns, and resources that can be found in an area no longer seem to be based on what you might expect to find based on the area’s geography and position on the planet.

Related reading: Another brilliant casual simulation game that everyone has to play is Mini Metro. Matt’s review.

That charm does gloss over something more sinister, and something that, of course, a game this lighthearted ignores completely. Namely, what happened in the real world when the real explorers from Europe discovered new continents and territories. The closest this game comes to addressing the genuine evil of colonialism is that some cities might not allow one of your less charismatic admirals to dock in the city. Of course, you can easily beat that system by having a high-charisma admiral dock instead, and then assign the low-charisma admiral to that fleet. And, despite the presence of the narrative, there’s no discussion in the game whatsoever about the morality of turning up to these villages and then exploiting their wealth by sending it back to Europe.

Still, it’s great fun to discover Atlantis, and then have your ships run into the tentacles of King Kraken. When I first saw this at TGS last year, I thought it was going to be a grander simulation game than it has turned out to be. In part I’m disappointed, because a hardcore simulation about exploring uncharted oceans in search of new land would be a fascinating game, but at the same time the simple, clean charm of Neo Atlas is really difficult to resist, especially when I’m in the mood to play something low-pressure while catching up on my movie or television backlog.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld