Review by Matt S.

Goichi Suda is, without a doubt, my favourite individual game maker out there. Relentlessly transgressive in how he approaches his work, Suda tears down walls with aplomb, and his healthy taste for the surreal and sublime alike mean that his work effortlessly displays a unique creativity; you know you’re playing a Goichi Suda game, even if you’re not aware of it before you start playing.

Related reading: On Lollipop Chainsaw, Goichi Suda’s subversive exploitation game.

That creativity and willingness to be different means his games aren’t always the most warmly received. Indeed, it means that a lot of his work is misunderstood completely. The most infamous example is Lollipop Chainsaw, an aggressively progressive game that was, from top to bottom, a deconstruction of a wide range of sexist tropes common to video games, and yet so many critics derided it as an example of what it was tearing down.

This is why I was concerned when I heard that Suda-san’s latest work, Let It Die, was going to be a free-to-play game. Because Suda’s games are polarising and often quite unpopular, they aren’t really compatible with the idea that free-to-play games need to have real mass market take-up in order to be profitable. My concern was that Suda would be pressured into compromising on his vision in order to make the game fit the monetisation model.

Note to self; if a treasure chest looks like a trap, IT IS A TRAP. Rookie error. #PS4share https://t.co/qfTYfQXhA7 pic.twitter.com/WdwOUs9NmR— Miku McMikuFace (@DigitallyDownld) December 4, 2016

Silly me. Goichi Suda doesn’t bow to pressure.

Let It Die is nothing short of a masterpiece of grindhouse surrealism, played within the context of a roguelike JRPG, which actually perfectly fits the theme. Throw in a skateboarding Death, a pole-dancing mushroom fanatic, and extreme gore, and you’ve got a game that can’t possibly be mainstream. I’m not sure if this thing is ever going to be profitable for that reason, but boy am I glad it exists.

You start the game with nothing but the goal of climbing up a tower filled with monsters and other creatures all sharing that same goal. Every single one of them wants your character dead on their own way to the top, so you’ll need to fight your way through hordes, hideous bosses, and other players on the way up a tower you’re not sure will ever finish. This combat isn’t the nice, bloodless, tap-tap battles like in a Final Fantasy game, though, oh no. This game is about sickeningly visceral battles where you’ll be carving into opponents with rotator saws, clubs with rusted nails punched through them, guns, and anything else that you can scavenge along the way. Characters explode into gory showers of crimson when killed, and it’s possible to perform executions on them that take full advantage of whatever weapon you’re carrying with you. Those executions rival Mortal Kombat for the raw pain that’s on display in the game.

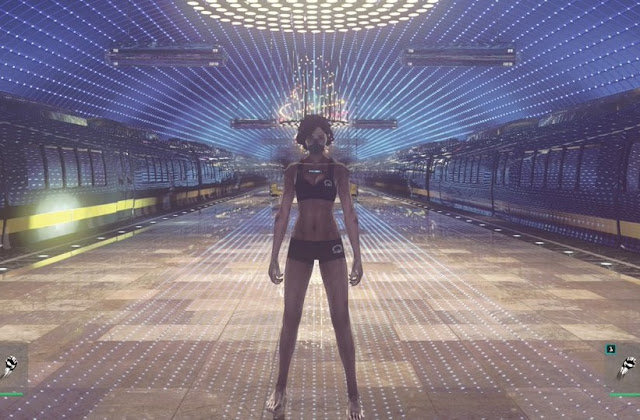

My first death. In true Suda fashion though, completely surreal. #PS4share https://t.co/qfTYfQXhA7 pic.twitter.com/ndAqLIy0za— Miku McMikuFace (@DigitallyDownld) December 4, 2016

Environments are grisly, decrepit, and reflective of the sheer violence going on around them. Every so often you’ll come across a named enemy – the avatar of another person somewhere out there playing the game too. These are tougher opponents, and are there because that other player sent them into your game to kill you. The multiplayer is not “live” – you simply assign a character to go on a looting mission while you’re away from the game – but it nonetheless reflects the dog-eat-dog world of Let It Die. Weapons degrade and are eventually destroyed, and it’s entirely possible that you’ll find yourself caught in a really difficult situation with nothing but your fists left. Mobbed by enemies, you’ll probably die, at which point you can use rare currency to revive your character, or let the character properly perish, in which case you’ll be returned back to home base with nothing, in true roguelike style. If you’re smart you’ll have a character return to base every once in a while to drop off some equipment into the storage chest there so that, in the very likely event that they do die, you’ll have something to pass on to your newly minted character in the next attempt.

This all has a purpose. We’re told at the start of the game that people try to ascend this tower to bring them “closer to God,” so naturally people trying to make the climb are acting like feral savages to one another. Though the game is more focused on raw gameplay than other Suda works (perhaps as a consequence of it being free-to-play, and therefore it’s only earning money when people are actively playing it), there are plenty of nuggets throughout the game pointing towards the transgressive platforms that inform most of Suda’s games. At home base you can wander into a bathroom that exists for no purpose whatsoever, but has had the wall between the men’s and women’s bathrooms torn down violently. Subtle it’s not, but then transgressive art rarely is.

Brought together, the game can best be described as quite ravishing. There’s a sublimity to the extreme violence that means the game transcends the mere act of doing violence; there’s a rhythm to it, and it behaves like a grisly dance that is quite transfixing to watch unfold. We’re told at the start of the game that no one’s ever actually survived to reach the top of the tower, so in turn we don’t rightfully know if there is a top of the tower. It’s therefore an absurdist and existential challenge whereby we’re meant to question whether there’s a point to what we’re doing at all.

— Miku McMikuFace (@DigitallyDownld) December 4, 2016

And therein lies Suda’s love of self-deprecation; you can easily read Let It Die as a satirical look at the pointlessness of free-to-play games, much as Fight Club or Manhunt make use of extreme violence to deconstruct their own relevant issues (capitalism and, well, capitalism, respectively). The violence of Let It Die is ridiculous, yes, and that’s precisely because Suda wants you to find it ridiculous and, one suspects, it’s because he strongly believes that free-to-play structures are ridiculous.

As an actual game Let It Die is of exceedingly high quality for a free-to-play title; it’s dozens of GB in download size and looks and feels every bit an example of a higher-end game from Japan. It’s also far too reasonable on the microtransactions and asking players for money. It’s possible to speed up progress through the game by paying real money, or preserve a favoured character that’s just perished but the incentives for doing that are low, particularly when anyone who is inclined to enjoy a roguelike is not going to have any issues with a grind, or re-starting games from scratch after a character dies.

I’ll be throwing a fair amount of money at Let It Die because I believe the game deserves a premium price, and Goichi Suda is a visionary game maker who has never failed to surprise and delight. This could so easily have been a senseless grind with no narrative context and hyperviolence for the sake of it, because the free-to-play monetisation model all but demands that’s what games are reduced to. But it’s not, and that’s testament to Suda’s ability to think well and truly outside of the box that he’s been able to pair this kind of unique creativity to that monetisation model.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld