“Auteur” is a word that I would argue is thrown around too much when it comes to video games. The theory behind it comes from film criticism, with the notion that a film is the director’s vision and solely their vision. When it comes to video games, though, it’s typically a team project and so the director’s vision is not his own. For me there’s really only one name that stands up to, and is worth of, the title of an auteur.

Related reading: You can read Sam’s review of the prequel to MGSV: The Phantom Pain, Ground Zeroes, here.

In all of his works, Hideo Kojima games are something that nobody else can emulate. To those who grew up with Metal Gear, often subtitled with “A Hideo Kojima Game”, Metal Gear has always been the extension of Kojima. It’s sad to see that Konami has refused to credit Kojima on the box of Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain, presumably a result of the very public split between the two, but it’s also sad that Konami has failed to understand why this subtitle was so important. Metal Gear has always delivered above and beyond as a piece of art. It’s more than just a game where you run around a base undetected, it’s a multifaceted experience that gives its author the well-deserved title of auteur. It is a Hideo Kojima game, and it should be recognised as such.

Unlike Metal Gear Solid 4, which was famous for extended cinematic movies that passed the length of some feature films, The Phantom Pain doesn’t take the same liberties with cinematic storytelling. Gone are the hour long cut scenes, and instead we’re provided with shorter and sharper moments that are spread throughout in the game. Although they might not be as long as some fans hoped for (because really after a while you learn to love how in love with themselves those cut scenes are), what we do see in The Phantom Pain are still some of the most powerful images available to witness in a video game.

And although The Phantom Pain has lost these big cinematic moments, the end results creates a much deeper connection between the player and the world of the game. A deep emotional attachment is forged, something that Kojima excels at maintaining throughout the entire campaign. Being forced to witness a helpless patient in a hospital ward being shot at point blank, only to then be given control and forced to crawl over his body immediately afterwards is horrifyingly raw, and something that is quite brave for Kojima to throw in there, as it does risk triggering some people. The Metal Gear series has always been absurd, over the top, and often controversial, not only in presentation, but its themes and characters. These close-up shots of the innocent victims of war that are showcased numerous times throughout the game somehow ground the idea of giant battle mechs and flaming goliaths and make it all so real. Warfare is human, and this realness brings this apparently farfetched world back into reality.

This realness is further demonstrated by how the inhabitants, mainly the soldiers of Afghanistan and Africa, interact. They’re presented as normal individuals in the way they’ll talk to one another whether it’s regarding the intruder that’s been seen around certain outposts, or something as throwaway as the weather. The Fox Engine is wonderful in bringing these characters to life to the point where as I was playing, members of my family assumed I was watching TV, rather than playing a game where these people weren’t real.

The Phantom Pain is set nine years after the destruction of Mother Base by the group XOF, which was focus of the main mission featured in last year’s prequel Ground Zeroes. “Venom” Snake, voiced by Kiefer Sutherland, known by fans of the series as Big Boss, wakes from his nine year long coma. This is all introduced in an incredible opening mission that serves as a great demonstration of how Kojima has developed his storytelling. Cut scenes are seamlessly intertwined with gameplay, which is itself longer than the entirety Ground Zeroes, and that sequence alone gives the player enough of a grasp on the story to get hooked.

Snake joins a mercenary group, known as Diamond Dogs, in order to track down the members of XOF. The Phantom Pain is set in 1984, during the Soviet-Afghan War and the Angolan Civil War. Snake travels to Afghanistan and Africa in his attempt to discover the members of the organisation Cipher, the mastermind behind Mother Base’s destruction.

Related reading: The best ten Metal Gear Solid moments (from 2013, so a little old now, but still).

Each mission is set within one of the two large open worlds, Afghanistan or Africa, with there being an incredible amount of freedom in how each mission is played out. For every objective in the game, there are perhaps 20 different ways to carry it out, and what’s great about having this gigantic playground is that it allows the player to experiment and have fun. While there still is a focus on tactical operations, stealth, and strategy, you’re more than capable of turning the game into a third-person shooter.

That being said, the stealth aspects of The Phantom Pain are beautiful when it plays out successfully. Tactical takedowns that occur after you sneak past the gaze of the seemingly never ending patrols is satisfying to say the least. When you make it to your objective without killing anyone, or alerting anyone to your presence is a thrilling achievement, and for someone like me, who makes Snake walk with two left feet, quite an achievement. And at the same time, I don’t really care when I make a terrible mistake and have the whole facility focus their entire arsenal on me, because it’s what I love about the game so much. When everything has gone so wrong, it’s a classic example of beauty in motion, because once again the Fox Engine showcases how real these soldiers seem. They’ll investigate, even fall in love with a decoy. They’ll follow the sound of footsteps or the trails of blood you’ve left behind. The AI is so smart, and so believable, I ended up seeing how many ways I could get caught just for fun. Although I was still there to extract a prisoner of war or eliminate a general, there were so many more things to do in this endless sandbox that I was happily getting distracted. And I loved it. I loved spending hours trying to hunt a bear. I loved spending hours (and I still haven’t managed to get it because of left foot Snake) trying to sneak into a heavily fortified area to grab the cassette tape of “Take On Me” so I could have it play when my chopper came to pick me up at the end of the mission.

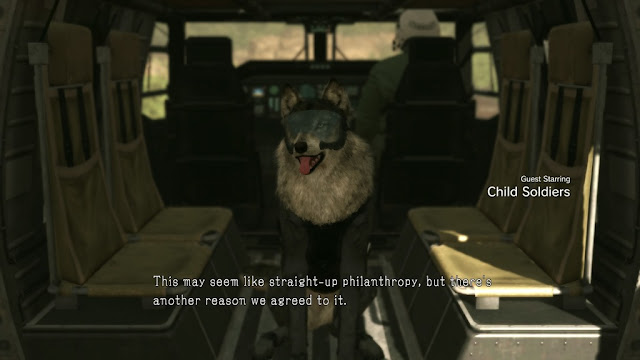

The Phantom Pain also introduces the buddy system, which allows for Snake to bring an ally onto the field of battle in every mission. These buddies; D-Horse, D-Dog and Quiet, all have different skills available to them, with discovering these skills and how to use them effectively assisting that experimental gameplay mentioned previously. D-Horse is Snake’s first buddy, and is merely a means of fast transport around the map. Both maps are huge, and it can take a very long time to walk to each destination. Having that speed does help new players, but it also makes Snake a very visible moving target. D-Dog can sniff out wildlife and enemies on patrol, and he can also attack enemies. Quiet, the deadly sharpshooter, can be used as a scout, and as a sniper as well to take out individual foes.

The Phantom Pain has a great cast assembled to take the roles of the primary characters. The most notable change is Kiefer Sutherland taking the role of Snake from David Hayter, and does a very good job of it. Going for an older voice is more fitting for big boss, and is also fitting for the overall narrative of The Phantom Pain. There’s an anguish in his voice, as Snake is obviously affected from the trauma of past events, meaning that whenever he does talk, it’s a stern yet, simple message. The rest of the cast deliver exceptional performances, and it also helps that motion capture was used in order to create the most realistic image possible. Screenshots don’t do The Phantom Pain justice. Down to individual grains of sand, this game is so detailed it’s picturesque. I didn’t mind the missions when I had to slowly crawl my way through a power plant, because it gave me time to look at even simple objects like cracked concrete slabs on the floor. Everything is so detailed, and its inclusion all works towards that overarching narrative of Snake in this war torn battlefield. Whether it’s walking past houses with the doors boarded up, sneaking past rows of sleeping child soldiers or discovering a village that was burnt to the ground, the mise-en-scene is perfect. Everything has been included for a reason, and if you dig deep enough, it reveals a much more personal backstory than any cut scene ever could.

There’s only so much I can write about, but this barely scratches the surface of what Metal Gear Solid V contains. There’s a massive catalogue of cassette tapes that both serve as a means of narration and as a music player. Side Operations that can play out as impressively as main objectives. A Mother Base which is perfectly capable of being an entirely different game in itself, which is focused on building a team to help Snake in the field. Not to mention a fully-fledged online mode that pits mother bases against each other, which is planned for release early next month. The Phantom Pain is one of the most ambitious games available to play. And it’s a masterpiece, in every sense.

Yes stealth games aren’t for everyone, but The Phantom Pain is so much more than a stealth game. What you are getting with Metal Gear Solid V is hours upon hours of the vision of one of the most creative and artistic directors in video game history.

– Sam M.

Contributor